Like many Indigenous people across Canada, Andrew Phypers, a criminal defence lawyer from the Lower Kootenay Band in the Canadian province of British Columbia, has a personal connection to residential schools.

His mother attended St Eugene’s Mission Residential School, where late last month ground-penetrating radar found 182 Indigenous children’s unmarked graves.

“I have lots of people in my community that attended the residential schools and can personally attest to the atrocities that did occur there,” Phypers told Al Jazeera in a recent phone interview. The unmarked graves at St Eugene’s were among several recent discoveries of hundreds of Indigenous children’s graves at the government-founded and church-run assimilation institutions.

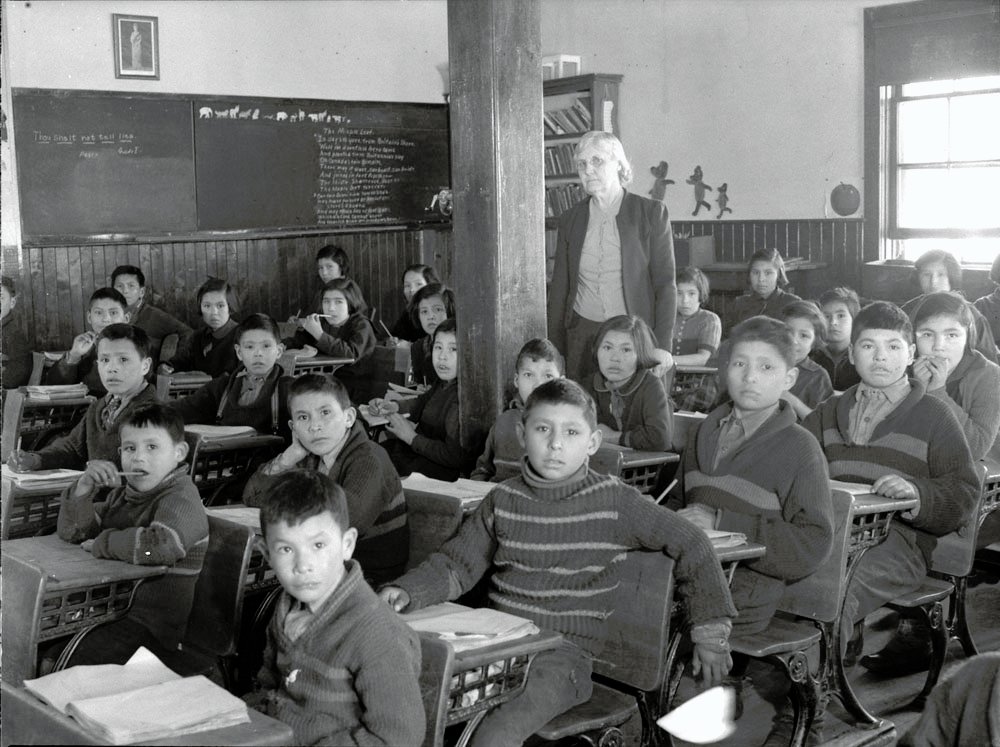

From the late 1800s until 1996, Canada removed 150,000 Indigenous children from their homes and forced them into institutions run by church staff where they had to cut their long hair and were forbidden from speaking their language and practising their culture. Many were physically and sexually abused. Thousands of children are believed to have died.

Canada’s goal was to kill Indigenous culture to make land and resources available to settlers. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a years-long process documenting survivors’ stories, concluded the practice was cultural genocide.

In 2016, the Canadian government identified more than 5,000 abusers, but to date, no individuals or institutions have faced charges under the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act, a federal law passed in 2000. A small number of priests were charged with sexual assault, but none have faced charges for homicide, according to lawyers familiar with the matter.

The recent discoveries of unmarked graves have spurred Indigenous groups and lawyers to demand that police lay criminal charges against the Canadian government, churches and individual perpetrators of crimes committed in the institutions.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) is behind a push for criminal charges, while Phypers is working with a group of lawyers to encourage the International Criminal Court (ICC) to open an investigation into the institutions. But experts say their efforts could be stalled or thwarted by the Canadian government.