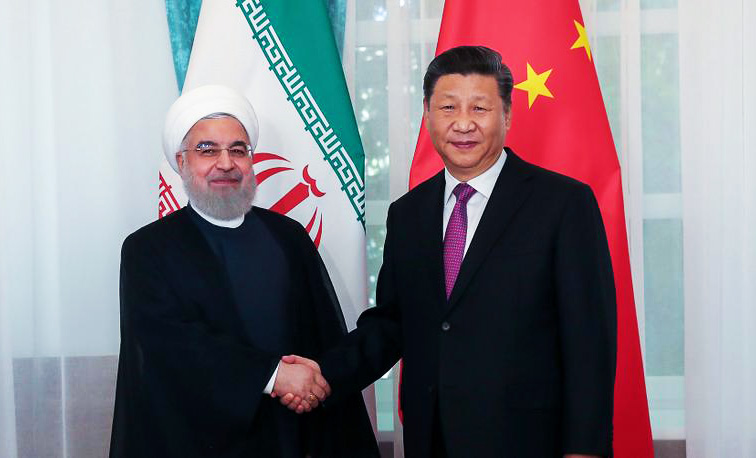

The recent Tehran deal signed between China and Iran has generated considerable hype about both its intended scope and its particular timing. Promising a quarter-century of strategic cooperation and long-term Chinese investment in Iran, the deal has been viewed with some alarm by a United States that views the slow-burning political and economic influence of China with misgivings.

More significant, however, is the deal’s timing, coming in a spring of diplomatic fluctuation for other Chinese allies such as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Given the particularly vague nature of the deal, it is likelier to be significant for the fact that it comes in a period of diplomatic uncertainty than it is as a strategic deal.

It is important not to overstate the significance of the Chinese-Iranian deal. China has made major investments in many countries across Asia and Africa, usually without much problem. Although it is fashionable in the West to speak of a Chinese economic colonialism, evidence for this is hard to come by. Rarely, too, do such long-term agreements ever match their hype. Twenty-five years is simply too long and uncertain a period to promise a strategic bilateral accord. In this case, the terms of the agreement are so vague and generalised that it is quite likely that the strategic cooperation will fade long before its official expiry.

The potential that the accord has for Iran’s economy, on the other hand, is significant. Iran was long able to bypass the United States’ sanctions because its relations with Russia, China, and even Europe were far friendlier. Indeed, to some extent these sanctions can be said to have unintentionally solidified the Iranian regime against internal opposition, which has historically come from a merchant class left much weakened after bearing the brunt of the sanctions.

The strategic opportunity that the United States unwittingly provided Iran after 2001 by toppling its adversaries in Baghdad and Kabul enhanced Iranian influence outside its borders. By the mid-2010s, Tehran, emboldened by its heady military adventures in Syria and later its role in the campaign against Daaish in Iraq, was able to approach talks over its nuclear programme with reasonable confidence, culminating in the 2015 Vienna Accord that sent alarm bells ringing for its rivals in Riyadh and Tel Aviv.

Yet Donald Trump’s maverick regime, egged on by Israel and Saudi Arabia, declined to honour treaty commitments made by his predecessor President Barak Obama. The Vienna Accord was scrapped, and Iranian militias in the region were confronted with increasing ferocity.

The cushion earlier afforded Tehran by the European Union, which had welcomed Iranian-American talks, was largely ineffective in shielding Tehran from Trump’s belligerence. The policy squeezed the Iranian economy hard enough to fill the streets with protesters in the late 2010s.

This provided an opportunity for China, already on friendly terms with Iran, to expand its influence much as the decline of American-Pakistani ties in the 2010s had played to Beijing’s advantage. Chinese investment is likely to make at least a short-term improvement in Iran’s economic fortunes.

The deal’s particular moment is also important, especially for Saudi Arabia, a regime traditionally viewed with suspicion by the liberal Democrats in the United States (though rarely to the extent of impairing important business) but heavily indulged by Trump.

This stemmed from traditional Saudi-American cooperation, traditional Saudi-Republican bonhomie, and also the very untraditional promise by Saudi crown prince Mohammad bin Salman to dispel, by hook or crook, the influence of the “radical Islam” that Washington saw as a threat.

As much because of Riyadh’s ties with Trump as anything, however, the then-opposition Democrats were obliged to condemn Saudi excesses. Joseph Biden, largely for public consumption, made a point of giving the Saudi crown prince a public reprimand both before and after he took over. This, again, did not impede the essential business between Washington and Riyadh, but when coupled with Biden’s relative openness toward compromise with Iran, deepened Saudi fears of diplomatic isolation.

Thus Saudi Arabia entered 2021 on far shakier ground than the past four years. Riyadh’s heavy entanglement with the United States meant that they simply could not risk a potentially hostile or unreliable incumbent in the White House. This was reflected in their dealings with Pakistan.

The historically strong links, in which Pakistani military and Saudi economic clout played a major role, had cooled off in the latter 2010s. Riyadh resented Pakistani ties with Iran, and Islamabad resented Saudi ties with India. Yet not long after Biden took power, a potentially weakened Saudi Arabia hurried to patch up its links with Pakistan.

Chinese-Iranian cooperation is thus likely to be viewed with similar dismay by Riyadh. Of course there is a difference: Saudi Arabia has never been as intertwined with China as it has with the United States, nor had any illusions about China’s traditionally friendly links with Iran, in contrast to American-Iranian links. Nonetheless, such is the extent of Saudi-Iranian hostility that any upgrade of relations with a major power can only provoke dismay in Riyadh.

There are now two important factors for the Saudi regime to consider. The first factor is the stance of the superpowers. Tensions seen in recent months with Washington are likely to be papered over, perhaps with further concessions to liberal sensibilities. China has never feigned concern about Saudi illiberalism, and so Riyadh’s incentive here will instead be to show Beijing how it can be a superior partner to Iran, perhaps through favourable economic deals.

The second factor is the Pakistani attitude: Will Islamabad see the agreement as a complement to the strong Chinese-Pakistani links, so that both Pakistan and Iran can participate in the Chinese-led Belt and Road initiative? Certainly this is the likely outcome, which gives Riyadh a motivation to try and hamstring this bonhomie without jeopardizing its own links to Beijing and Islamabad.

The Saudis are likely to finger the oft-tense bilateral relations between Pakistan and the Iranian regime. Should that fail to work, the Afghan conflict – where Pakistan and Iran share China’s unease over continued American dominance – might present a more fruitful avenue, whether by steering it in a less Iran-friendly direction or by militating against American withdrawal.

Thus, while the Chinese-Iranian deal may not have much of an impact in the strategic sense, the diplomatic challenge it presents for the United States, Israel, and especially Saudi Arabia is likely to have repercussions in the region.