The XEC variant has emerged in 27 countries, including France and the U.S., infecting over 600 individuals. As a new coronavirus variant sweeps through Europe and North America, health officials are urging increased monitoring of its spread.

XEC has primarily affected regions just as the winter season approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, a time when respiratory illnesses typically rise. Although XEC appears to spread more easily than previous COVID variants, the cases have not been as severe as those experienced during the height of the pandemic.

Understanding the XEC Variant

XEC is a “recombinant” version of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19. Recombinants occur when a person is simultaneously infected with two different COVID strains, leading to the exchange of genetic material and the creation of a new strain. While symptoms reported from XEC infections have been mild, it is part of the Omicron lineage, which peaked in severity in 2022.

Each variant develops unique mutations characterized by distinct “spike proteins” that allow the virus to enter human cells. Omicron has given rise to several subvariants, with XEC being formed from two of these—KP.3.3 and KS.1.1—both of which evolved from the earlier JN.1 variant that was dominant globally in early 2024.

Recombinant variants like XEC are not unprecedented; the XBB recombinant variant was the leading cause of COVID cases in 2023.

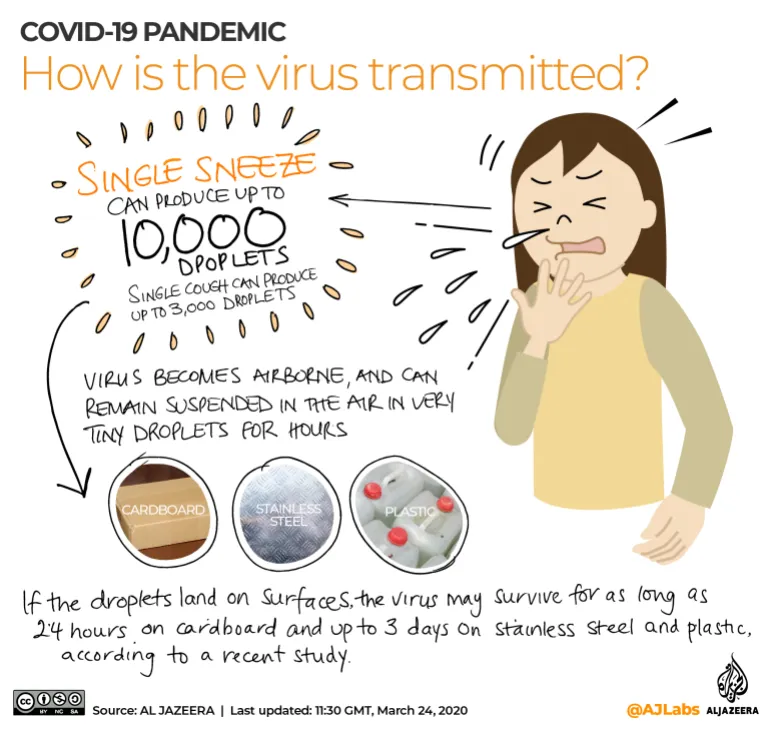

How XEC Spreads

XEC primarily transmits through respiratory droplets released when an infected person breathes, talks, coughs, or sneezes. Although the virus can survive on surfaces, airborne transmission is the more common route. Public health officials recommend measures such as social distancing, wearing masks in public, and using hand sanitizer to mitigate the spread.

XEC is believed to spread more easily than earlier variants, likely due to its unique spike proteins that enhance its ability to enter and replicate within human cells. Ongoing studies are examining its exact transmissibility.

Symptoms of XEC

Common symptoms associated with XEC include sore throat, fever, fatigue, and muscle aches. These symptoms are generally mild and may appear within two to 14 days post-infection. Severity varies, with some cases being asymptomatic and others more pronounced, particularly in high-risk populations such as the elderly.

Currently, XEC does not seem to cause any unique symptoms or more severe effects compared to other COVID variants.

Detection of the New Strain

XEC was first identified by researchers in Berlin, Germany, in August, based on COVID-19 samples collected in June. The delay in detection may have been due to sequencing backlogs as focus was directed towards other dominant variants at that time.

Global Spread of XEC

Since its detection, XEC has been reported in 27 countries, with over 600 cases documented according to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). France accounts for more than 21% of these cases, with the variant also gaining traction in the U.K., Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany. In the U.S., over 100 cases have been reported across 25 states.

However, the actual spread may be larger, as not all countries regularly report data to GISAID.

Assessing the Danger of XEC

So far, evidence suggests that XEC is not significantly different or more dangerous than other Omicron subvariants. The World Health Organization has yet to classify XEC as a “variant of interest.”

As is common with respiratory viruses, COVID-19 and its variants are expected to circulate more widely during the fall and winter months when people spend more time indoors. Experts anticipate that XEC may peak in late October or November, primarily in Europe and North America.

Initial studies indicate that existing vaccinations remain effective against the XEC variant. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the U.S. recommends that everyone aged six months and older receive the updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccine, regardless of prior vaccination status.