The first virus to have its genome read was an obscure little creature called ms2; the 3,569 RNA letters it contained were published in 1976, the hard-won product of some ten years’ work in a well-staffed Belgian laboratory.

The SARS–COV-2 genome, almost nine times longer, was published just weeks after doctors in Wuhan first became concerned about new pneumonia. That feat has since been repeated with getting on for 1m different samples of SARS–COV-2 in the hunt for fearsome variants like the one ravaging Brazil.

Within weeks of its publication, the original genome sequence became the basis for the vaccines that today are stymieing the virus wherever supplies, politics, and public confidence allow.

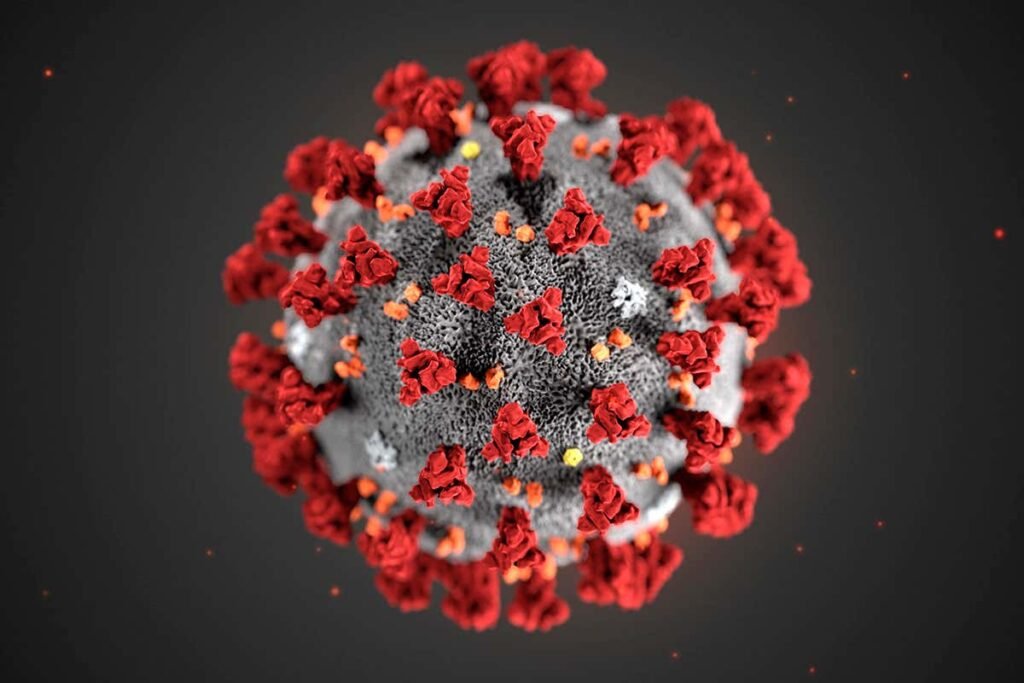

The cover of ‘The Economist’ this week describes how sudden, concerted action against covid-19 has brought together decades of cumulative scientific progress. The spate of data, experiments, and insights has had profound effects on the pandemic—and, indeed, on the future of medicine.

Around the world, scientists have put aside their own work in order to do their bit against a common foe. Covid-19 has led to some 350,000 bits of research, many of them on preprint servers that make findings available almost instantaneously.

The basis of all this is the application of genetics to medicine in a systematic and transformative way—not just in understanding the pathology of diseases but in tracking their spread and curing and preventing them.

This could underpin what is becoming known as “natural security”: the task of making societies resilient in the face of risks stemming from their connection to the living world, whether because of disease, food insecurity, biological warfare, or environmental degradation.

The pandemic has shown that biomedical science has the tools and the enthusiasm to improve the world. The world must now build on both.

Courtesy: The Economist