Two teenagers from Woodlands, Texas, have invented a device aimed at tackling one of the most widespread and challenging forms of pollution: microplastics. These tiny plastic particles are found everywhere—from the depths of the ocean to the peak of Mount Everest—and are present in household dust, food, and water.

Estimates suggest that people ingest and inhale the equivalent of a credit card’s worth of plastic each week. This plastic can accumulate in various parts of the body, including the lungs, blood, breastmilk, and testicles.

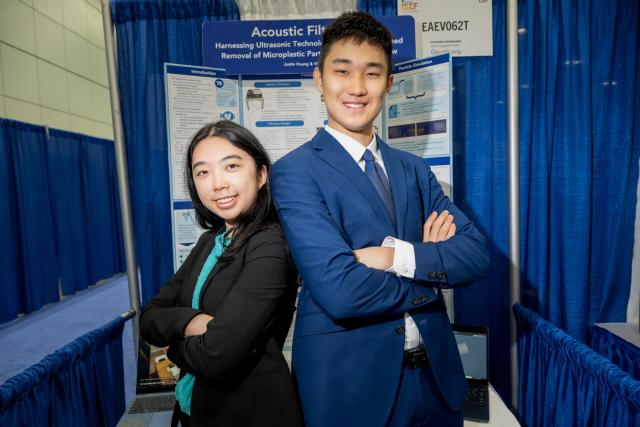

Victoria Ou and Justin Huang, both 17, aspire to mitigate this problem with their innovative device that removes microplastics from water using ultrasonic (high-frequency) sound waves. Their invention is the first to successfully employ this method.

Ou and Huang showcased their project at the recent Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) in Los Angeles, an event that brings together top competitors from science fairs around the world to compete for $9 million in prizes.

The Texas duo won first place in their Google-sponsored category, Earth and Environmental Sciences, and also received the $50,000 Gordon E. Moore Award for Positive Outcomes for Future Generations.

Although the ultrasonic technique is still in its early stages, these high schoolers hope that one day it will be able to filter microplastics from drinking water as well as from industrial and wastewater released into the environment.

“This is the first year we’ve worked on this,” Huang shared with Business Insider backstage after receiving their award. “If we could refine the process—perhaps using more professional equipment and conducting experiments in a lab rather than at home—we could significantly improve our device and prepare it for large-scale manufacturing.”

While the exact impact of microplastics on human health remains unclear, many common chemicals in plastics have been linked to increased risks of cancer, fertility and developmental issues, and hormone disruption. Despite this progress, eliminating microplastics from the environment is still a distant goal.

Last fall, while brainstorming ideas for their ISEF project, Ou and Huang visited a water treatment plant to investigate whether such facilities already had tools to remove microplastics from wastewater.

They discovered that the answer was no. The employees informed Huang and Ou that because the EPA doesn’t regulate microplastics, the facility does not remove them from wastewater.

“We knew from that moment we needed to focus on this issue,” Huang told Business Insider.

Even if the EPA started regulating these persistent plastic particles tomorrow, existing removal methods have significant drawbacks, Huang explained.

One approach involves using chemical coagulants, like aluminum hydroxide, which, when added to water, cause microplastics to clump together into larger, more easily filtered chunks. However, chemical coagulants can also pollute the environment and alter the pH of purified water. Additionally, they are expensive.

Some physical filters are available, but they tend to clog easily. Biological solutions, such as using enzymes to break down plastics, are not efficient enough to address this problem on a large scale.

“We wanted to find a solution because current methods aren’t really effective,” Huang said.

Thus, Ou and Huang—friends since elementary school with a shared interest in the environment—set out to invent their own environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and efficient solution.

Huang and Ou’s device is remarkably compact, roughly the size of a pen. It consists of a long tube with two stations of electric transducers that use ultrasound to function as a two-step filter.

As water flows through the device, the ultrasound waves create pressure that pushes microplastics back while allowing the water to flow forward, Ou explained. The result is clean, microplastic-free water.

The two teens tested their device on three common types of microplastics: polyurethane, polystyrene, and polyethylene. According to a press release, their device can remove between 84% and 94% of microplastics from water in a single pass.

Ou and Huang believe their technology could be applied in wastewater treatment plants, industrial textile plants, sewage treatment plants, and rural water sources. On a smaller scale, it could filter microplastics in laundry machines and even fish tanks.

However, more work is needed. “To reach that stage, I think we need a lot more processing,” Ou said. “This is a pretty new approach. We found only one study attempting to use ultrasound to predict the flow of particles in water, but it didn’t completely filter them out yet.”

Huang agrees. “I hope we can scale this up, but first we need to refine it because this technology is still in its infancy,” he said.

Their $50,000 prize could help them achieve this goal. In the meantime, they are enjoying the moment.

“We were just happy to go to ISEF. Originally, we didn’t expect much, but winning first place and the top award is more than we ever imagined,” Ou said.

“This is something I’ve dreamed of my whole life, so I’m still pinching myself trying to figure out if this is real or not,” Huang added.