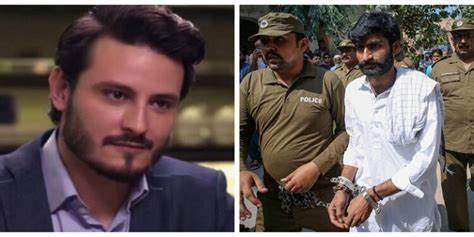

“Sketchy,” “illegal,” and “contradictory to the law” are just a few of the words used to describe Osman Khalid Butt’s Supreme Court challenge to the acquittal of Qandeel Baloch’s brother, who was acquitted in her murder case on Monday.

Barrister Khadija Siddiqui filed the appeal under Article 184(3) of the Constitution, pleading for the Supreme Court to overturn the Lahore High Court’s acquittal of Muhammad Waseem for the murder of his sister and reinstate the conviction of the trial court declaring him guilty.

After being found guilty of the alleged honour killing of Baloch in 2019, a Multan model court convicted Waseem and sentenced him to life in prison. Earlier this month, the LHC found him not guilty of all charges against him.

After the acquittal, Maleeka Bokhari, Pakistan’s Parliamentary Secretary for Law and Justice, claimed that the law ministry was planning to appeal the ruling.

It was said in a plea filed on Monday before the SC that when Waseem moved to have his sentence overturned at the LHC, the LHC had acquitted him because of a “compromise.”

It was claimed in the appeal that the ruling of the LHC “enabled the perpetrators of honour killings to evade prosecution by requesting forgiveness,” and “basically encourages such brutality.” So because of the assailed judgement “the everlasting gap which assumedly had been corrected by the Criminal Law Amendment (Offences in the Name or Pretext of Honour) Act, 2016, stood invalidated,” it stated.

According to the petition, the acquittal “disrespects fair application of law and weakens the general public’s confidence, faith, and trust in our criminal justice system,” it stated.

The petition described the LHC’s decision as “sketchy, unlawful, wrong in the light of law” and “liable to be set aside” and outlined other issues that should be reconsidered. High Court judge “failed to properly analyse established norms regarding acquittal” and “arbitrarily and incorrectly” accepted “without grasping the relevant facts of the particular case,” according to the petition.

“Misreading and non-reading of the content in the file” got attributed for the decision.

Although the accused was given an opportunity to present their side of the story, the petition claimed that the court “diminished salient details, which made the prosecution case reliable and trustworthy.” It also claimed that the evidence available to incriminate the accused was not utilised to its fullest extent.

According to the argument, Waseem’s conviction under Pakistan’s fasad-fil-arz (misconduct on earth) concept did not apply to this particular instance since it was an honour killing. Perpetrators can no longer beg forgiveness from the victim’s family (and occasionally their own family) and have their sentences reduced under a recent legislation amendment.

However, whether a murder gets defined as a crime of honour is left to the judge’s discretion, meaning killers can theoretically claim a different motive and still be pardoned.

After waiving or compounding the right of Qisas (retribution), “there is no requirement under law to document evidence to determine the question of Fasad fil arz (retribution), in particular, when Section 311 PPC, unfolds that the facts and circumstances of a particular case call for the punishment of an offender under Section ibid against whom the right of Qisas has been waived or compounded,” the petition said.

There had been an agreement, but “the court was not to blindly and hastily rely upon that compromise in order to acquit the accused,” the petition to SC stated. It reiterated that a judge “should apply his judicial intellect to the facts and circumstances of the case, to convict the accused on the principles of fasad fil arz”.

To prove that an issue of fasad fil arz exists, the petition argues that the judge “erred in his observation”. Furthermore, it stated that the LHC judge “falsely understood” that Section 311 PPC did not apply because the defendants reached an agreement before the accusations were framed.

According to the judge’s ruling, “the defendant was entitled to his acquittal because of the judge’s error in determining that there had been a combination of offences.”

Waseem was acquitted after the judge, according to the petition, made an “outright violation” of the applicable norms of law by acting “blindly and hastily” on that compromise.

Waseem willingly admitted to the crime, according to the plea, which said that there was enough evidence to condemn him. Because of this “misinterpretation and misapplication of the law, and the resultant grievous miscarriage of justice,” the LHC found that Waseem was acquitted.

According to the plea, the judge’s decision is “laden with major faults and infirmities,” and if it is not overturned, the appellant would suffer “irreparable harm.”