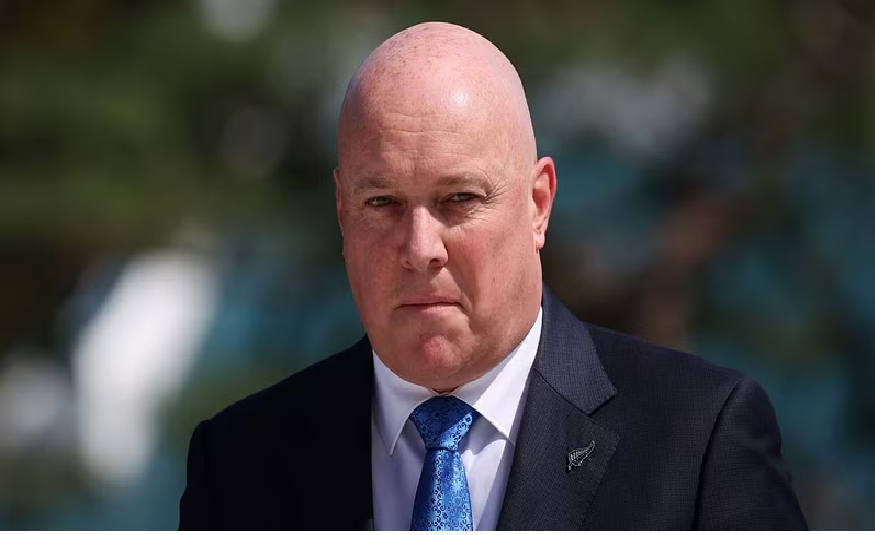

On Tuesday, New Zealand Prime Minister Christopher Luxon issued an unprecedented and “unreserved” apology to survivors of abuse in state and church-run care spanning seven decades, covering much of the nation’s post-independence history.

Many survivors were from the Indigenous Māori and Pacific Islander communities, historically affected by colonization and racial discrimination for almost two centuries.

What triggered Luxon’s apology?

Luxon’s apology follows the July report from New Zealand’s Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, which revealed that one in three individuals in state or church care from 1950 to 2019 experienced abuse. Around 200,000 children, youth, and vulnerable adults faced physical and sexual abuse, with over 2,300 survivors providing testimonies.

The commission documented severe abuse practices, including the use of weapons and electric shocks, with harrowing cases from Lake Alice psychiatric hospital, where victims endured sterilization, unethical medical experimentation, and electric shock treatments.

Recommended Actions

The commission made 138 recommendations, urging formal apologies from the government and heads of the Catholic and Anglican churches. It also proposed incorporating the Treaty of Waitangi and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into policy to enable Māori people to organize under their traditions.

So far, New Zealand’s government has taken steps on 28 of these recommendations and plans to implement additional measures, such as better monitoring to prevent abuse in care facilities.

Disproportionate Impact on Indigenous Communities

The report highlighted that abuse disproportionately affected Māori and Pacific Islander communities, often forcibly separated from their cultural practices and families in care facilities. Māori children suffered particularly harsh treatment, experiencing racial discrimination and detainment when found in public places. Practices like “pepper potting,” where Māori families were encouraged to live in predominantly white areas for assimilation, further disconnected them from their communities.

Mixed Responses to Luxon’s Apology

Many Māori survivors expressed that the apology alone is inadequate. Some criticized the lack of Māori input in the apology’s drafting and the omission of the Treaty of Waitangi from Luxon’s address. Survivor Ihorangi Reweti-Peters, recently released from state care, questioned why Māori traditions were not acknowledged in the apology.

Māori political writer Rawiri Taonui described the abuse as “cultural genocide,” pointing to the extensive abuse of Māori children in care.

What Makes an Apology Meaningful?

Critics, including survivors, noted that the apology’s setting in parliament limited the presence of those affected, with only 180 seats available for over 2,300 survivors. While the apology was livestreamed to four venues, these could only accommodate 1,700 people, and attendees were selected by ballot.

Church Involvement

Luxon’s apology also addressed abuse in church-run institutions. However, there is currently no structured financial redress plan, though Luxon urged church leaders to contribute to the redress process.

Comparatively, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report in 2015 classified the abuse of Indigenous communities as “cultural genocide” and included financial reparations, although the Catholic Church did not fully meet its financial obligations.

New Zealand’s Reparations History

For decades, Māori communities have sought compensation for lands seized by colonizers. The islands, known as Aotearoa, were renamed New Zealand under British rule in 1840. Despite financial reparations promised by Queen Elizabeth in 1995, many Māori felt these were insufficient, considering the extensive loss of land. By 2022, at least 40 compensation settlements remained unresolved.

For survivors of state abuse, expectations for redress from New Zealand’s government are tempered by economic constraints. According to David MacDonald, a political science professor and Royal Commission Forum member, New Zealand’s economy is unlikely to support the level of financial compensation offered to survivors in larger economies like Canada or Australia.