Over the past several decades, the role of International non-Governmental Organisations has shifted from the periphery of global political affairs to its core. International non-governmental organizations have established themselves as critical non-state actors in the liberal world order, assisting in development at various levels in various states, with or without the backing of the state. In many instances, they have been able to contribute significantly to the global peace efforts, and as per statistics, their numbers have increased by 500% since the 1990s. As per Séverine Autesserre, they form part of the worldwide Peace Inc., an industry that has emerged with the rise of conflicts; an industry that thrives on the end of historical ideologies, based on an increase in the number of religious and social conflicts; and an industry focused on peace-making, peacebuilding, organising awareness and conflict resolution seminars, trying to bring on incremental peace – all that is at the behest of its donors. However, a critical examination reveals that this industry is incapable of establishing lasting peace in conflict zones.

According to the numbers, this industry has raised over two billion dollars in donations since the start of the Afghan War. According to Joshua Craze, they collected this sum between 2002 and 2012. That is more than the GDP of small island states. However, even after the US withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021, the Afghanistan Peace Process failed, although the US had gathered a large number of organizations, particularly those working for Afghans. The funds and donations are great, undoubtedly, and if we go by the monetary patronage, Peace Inc. is powerful and can do substantial services where it is needed. However, the question is why it does not?

International nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) have assisted and convened conversations in nations ranging from Syria to Yemen to Iraq to Afghanistan, but could not achieve meaningful or gradual change. The violence and local grievances remain, and the conditions have become worse than before the wars. Séverine Autesserre argues it is because most INGOs use a top-to-bottom approach in conflictual situations. They cannot understand what the on-ground realities are because most workers are not local; they are not allocating funds as per the needs of locals; they cannot hire experienced locals to understand their grievances. According to her, it is frequently as if a Kazakh national travelled to the United States to improve the race or arms situation, despite the fact that he does not comprehend the culture or language. In sum, these organisations ignore the locality and context.

This shows a significant failure of INGOs, as there are persistent conflictual situations in the Middle East, Afghanistan, and other areas where people are battling civil and political conflicts, but INGOs have increased their spending, squandering years of financial assistance and resources as violence persists. Séverine Autesserre has criticised the industry of INGOs for not putting more effort into creating actual peace because of their ignorance of on-ground realities.

An overabundance of International Relations scholars have tried to give a critical perspective on the work that INGOs do, such as Paul D. Williams, Syed Ehtisham, and Justin Rosenberg. Many states feel that their “non-governmental” foundation is just an illusion. Many call it a misnomer. Such authors have enlisted the help of those with power and authority to bring such organisations into being. For example, during the Cold War and the Arab Uprisings, the US manipulated the National Endowment Fund by funding foreign non-state organizations to wage war on Communist and Arab regimes. They would conceal this cash in the wages of their employees or through some other strategy.

To be precise, the US-funded INGOs in Egypt supported the interests of an imperialist power. Similarly, during the Afghanistan War, while the US was waging drone attacks and missiles, organisations like Seeds of Peace and USIP were publishing research reports that viewed the issues in Afghanistan in isolation from the War on Terror. It bribed them to declare that local issues, not the US War on Terror, were to blame for Afghanistan’s devastation.

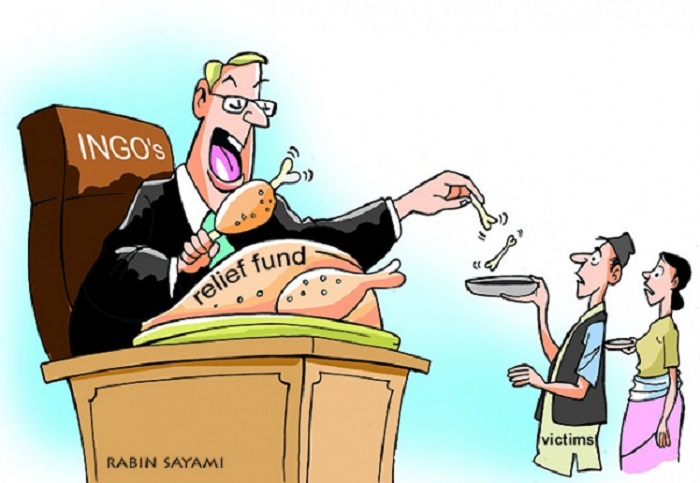

Without a doubt, the international liberal world order values the work of NGOs. They have been a great help to individuals for the fulfilment and awareness of their rights, to the states in various development projects, to the cohesion of states, and for the promotion of peace, state cooperation, and interdependence, as per Sara Michel. Their normative and social reach are powerful in generating momentous change, but not all apples are good. There are various examples of INGOs becoming so powerful that they displace state regulations (such as the ones working on climate change), undermine state sovereignty, or go to conflictual areas just to fill their own pockets.

This issue of funding, as discussed above, is also crucial. Sure, every organisation wants funds and monetary backing. But these funds limit them. They have to work the way their donors want them to. This sometimes leads to them ignoring actual issues, diffusing local issues, and focusing from top to bottom. Other times, they work with a systematic agenda of propaganda and targeted campaigns to spread mutiny, as seen during the Arab Uprisings, particularly in Egypt. This highlights the need for a balance of power between states and non-state actors. It poses the question of how powerful an INGO should be.

Alternatively, most of these INGOs are formed around shared values and sensitivity to some particular issues. For instance, some INGOs work particularly for health, or rights, or particularly for women’s education, or particularly for disabilities, or something along these lines. Many researchers have argued that the shared values of an organisation are integral to its structure and crucial to its productivity and effectiveness. But if the structure of the shared value is weak, then they do not perform the work they intend to do. To critically understand the role of INGOs, we also examined their shared values. Their success depends on their shared values.

A critical perspective on INGOs, therefore, raises questions about their existence, who created them, what work they do, are they doing what they aimed to do, where do they get the most funding from, where are they situated, and are they doing what they aimed to do. But there is still a need for a lot of research on the case of INGOs because of questions like why some INGOs have been successful in India and Nepal while advocating for health but not in North America and Haiti while advocating against genital mutilation in girls? And why are some INGOs successful in creating peace in Rwanda but not in Congo or Somalia?

Works at The Truth International Magazine. My area of interest includes international relations, peace & conflict studies, qualitative & quantitative research in social sciences, and world politics. Reach@ [email protected]