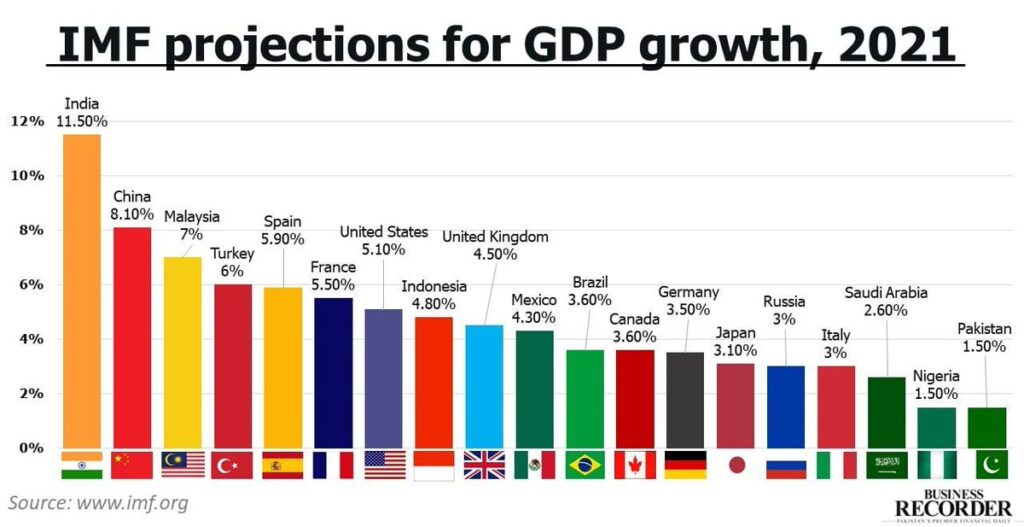

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Tuesday forecast a subdued economic growth rate of 1.5% for Pakistan, coupled with a higher rate of inflation and rising unemployment, during the current fiscal year. This was against the recent World Bank forecast of 1.3% growth rate. They do not see any speedy economic turnaround in Pakistan, with public debt peaking a whopping 94% size of the nation’s economy in the current fiscal year.

The 1.5% growth projection by the IMF is in stark contrast with revised 3% GDP growth forecast made by the State Bank of Pakistan a few days ago. The IMF estimates are in line with those of World Bank, which has projected growth at 1.3% for current year.

In its World Economic Outlook (WEO) 2021 report, the Washington-based lending agency has projected 8.7pc average rate of inflation, current account deficit at 1.5% of GDP and unemployment rising by 0.5% to 5% during current fiscal year. This is in sharp contrast with targets set by the government for the current year at 2.1% for GDP growth rate, 6.5% rate of inflation and 1.6% for current account deficit.

Going forward, the IMF has projected economic growth rate recovering to 4% of GDP next year (FY2022) and 5% by 2026. It says inflation rate would come down from 10.2% last year to 8% year on year and 10% on average by FY2022. The Fund estimates current account deficit rising from 1.1% of GDP in FY2020 to 1.5% in FY2021 and then going up to 1.8% of GDP in FY2022 and peak at 2.9% of GDP by 2026.

The WEO projects global growth making a strong recovery to 6pc in 2021, 0.8 percentage point above the June 2020 forecast. “After an estimated contraction of –3.3pc in 2020, the global economy is projected to grow at 6% in 2021, moderating to 4.4% in 2022,” it says.

The contraction for 2020 is 1.1 percentage points smaller than projected in the October 2020 WEO, reflecting the higher-than-expected growth outturns in the second half of the year for most regions after lockdowns were eased and as economies adapted to new ways of working.

The projections for 2021 and 2022 are 0.8 percentage point and 0.2 percentage point stronger than in the October 2020 WEO, reflecting additional fiscal support in a few large economies and the anticipated vaccine-powered recovery in the second half of the year.

According to the report, global growth is expected to moderate to 3.3% over the medium term — reflecting projected damage to supply potential and forces that predate the pandemic, including aging-related slower labor force growth in advanced economies and some emerging market economies.

Thanks to unprecedented policy response, the Covid-19 recession is likely to leave smaller scars than the 2008 global financial crisis. However, emerging market economies and low-income developing countries have been hit harder and are expected to suffer more significant medium-term losses, the WEO observes.

The IMF estimates 5.1% growth during 2021 for advanced economies including 6.4% for the euro area, 3.3% for Japan and 5.3% for UK. The growth prospects for emerging market and developing economies are put at 6.7% led by 12.5% for India and 8.4% for China.

Nonetheless, the outlook presents daunting challenges related to divergences in the speed of recovery both across and within countries and the potential for persistent economic damage from the crisis. Yet, even with high uncertainty about the path of the pandemic, a way out of this health and economic crisis is increasingly visible, thanks to the ingenuity of the scientific community that produced multiple vaccines that can reduce the severity and frequency of infections.

In parallel, adaptation to pandemic life has enabled the global economy to do well despite subdued overall mobility, leading to a stronger-than-anticipated rebound, on average, across regions. Additional fiscal support in some economies, especially the United States — on top of an already unprecedented fiscal response last year and continued monetary accommodation — further uplift the economic outlook.

The divergent recovery paths are likely to create significantly wider gaps in living standards between developing countries and others, compared to pre-pandemic expectations, the IMF says, explaining that cumulative per capita income losses over 2020–22, compared to pre-pandemic projections, are equivalent to 20% of 2019 per capita GDP in emerging markets and developing economies (excluding China), while in advanced economies the losses are expected to be relatively smaller, at 11%. “This has reversed gains in poverty reduction, with an additional 95 million people expected to have entered the ranks of the extreme poor in 2020, and 80 million more undernourished than before”.

The WEO notes that multi-speed recoveries are under way in all regions and across income groups, linked to stark differences in the pace of vaccine rollout, the extent of economic policy support, and structural factors such as reliance on tourism. Among advanced economies, the United States is expected to surpass its pre-Covid GDP level this year, while many others in the group will return to their pre-Covid levels only in 2022. Similarly, among emerging market and developing economies, China has already returned to pre-Covid GDP in 2020, but many others are not expected to do so until well into 2023.

The contraction of activity in 2020 was unprecedented in living memory in its speed and synchronized nature. But it could have been a lot worse. Although difficult to pin down precisely, IMF staff estimates suggest that the contraction could have been three times as large if not for extraordinary policy support.