Dark Oxygen

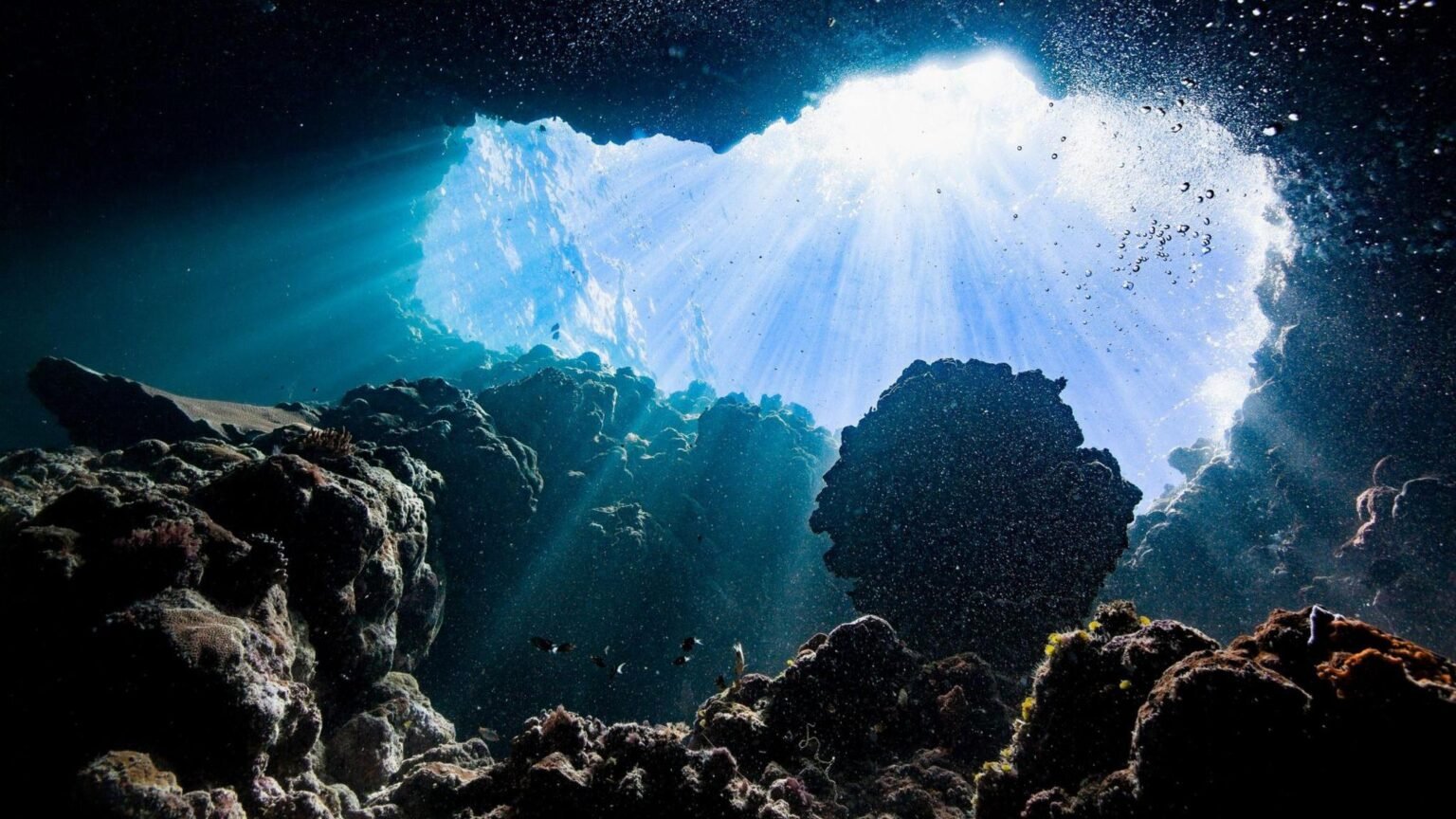

In a groundbreaking yet controversial discovery, scientists have proposed that metallic rocks found in the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean could be producing oxygen without the need for sunlight. This phenomenon, referred to as “dark oxygen,” has sparked intense debate within the scientific community and raised concerns among environmentalists and mining companies.

The discovery was first published in the journal Nature Geoscience in July 2023. Researchers suggested that polymetallic nodules — potato-sized rocks scattered across the seabed — might be generating electrical currents capable of splitting seawater into hydrogen and oxygen through a process known as electrolysis.

This finding challenges the long-held belief that oxygen production on Earth began with photosynthesis around 2.7 billion years ago when organisms started using sunlight to produce oxygen.

The discovery was made in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a vast area of the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii, which is rich in manganese, nickel, and cobalt — metals essential for electric car batteries and other green technologies. Mining companies have shown great interest in this region, but environmentalists warn that deep-sea mining could cause irreversible damage to fragile ecosystems.

Greenpeace, which has been actively opposing deep-sea mining in the Pacific, said this discovery highlights how little is known about life in these extreme environments. They argue that this finding further supports the need to halt deep-sea mining to protect delicate marine ecosystems.

However, the study, led by marine ecologist Andrew Sweetman, has faced significant criticism from other scientists and mining companies. The Metals Company, a Canadian deep-sea mining firm that partially funded the research to assess the ecological impact of mining, dismissed the findings, calling them the result of “poor scientific technique and shoddy science.”

Several scientists have also expressed doubts about the validity of the research. Since July, five academic papers have been submitted for review, refuting Sweetman’s conclusions. Matthias Haeckel, a biogeochemist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Germany, stated that the study lacked clear proof and left many questions unanswered. He emphasized the need for further experiments to either confirm or disprove the findings.

Olivier Rouxel, a geochemistry expert at France’s Ifremer institute, also questioned the results, suggesting that the oxygen detected could be from air bubbles trapped in the measuring instruments.

He was skeptical that nodules, which take millions of years to form, could still produce enough electrical current to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. “How is it possible to maintain the capacity to generate electrical current in a nodule that is itself extremely slow to form?” he asked.

In response to the criticism, Sweetman acknowledged the scientific skepticism and said he was preparing a formal response. He noted that such debates are common in the scientific world and help advance knowledge on complex subjects.

The discovery of “dark oxygen” has not only divided scientists but also intensified the debate on deep-sea mining, with environmentalists calling for a halt to protect the ocean’s delicate ecosystems. Whether this phenomenon will be proven or debunked remains to be seen, but it has certainly shed light on how much remains unknown about the mysterious depths of our oceans.