A comprehensive analysis of lunar gravity, using data from two NASA spacecraft, is shedding new light on why the moon’s two sides—the near side always facing Earth and the far side facing away—appear so different.

Findings from NASA’s GRAIL (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory) mission reveal that the moon’s internal structure is asymmetrical, likely due to intense volcanic activity on the near side billions of years ago, which shaped its surface features.

The study shows that the near side of the moon undergoes more tidal flexing—deformation caused by Earth’s gravitational pull—than the far side. This suggests differences within the moon’s mantle, the internal layer between its crust and core.

“Our research demonstrates that the moon’s interior isn’t uniform. The side facing Earth is warmer and more geologically active than the far side,” said Ryan Park, lead author of the study and head of NASA’s Solar System Dynamics Group at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The findings were published Wednesday in Nature.

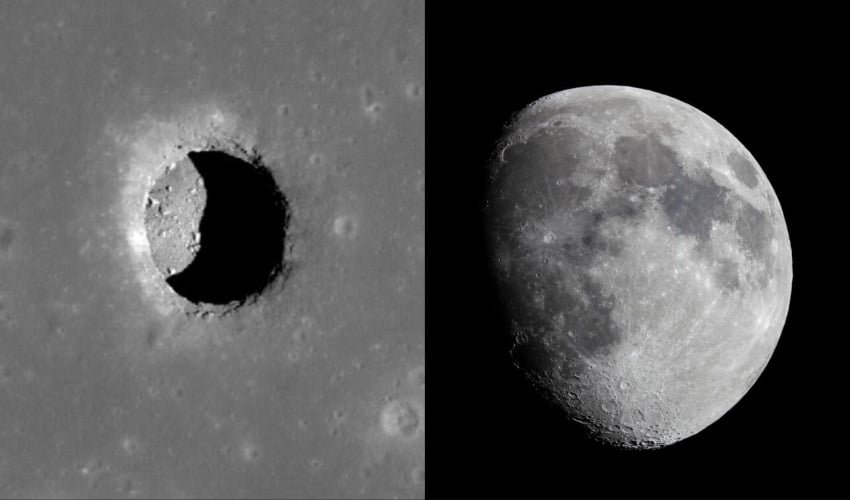

The near side features vast basaltic plains, known as maria, formed by ancient lava flows. In contrast, the far side is heavily cratered and rugged, with few such plains.

Scientists had long suspected that concentrated volcanic activity on the near side led to the accumulation of heat-producing radioactive elements like thorium and titanium in its mantle. The latest study offers the strongest evidence yet to support this theory.

Researchers estimate that the near side’s mantle is roughly 100–200°C (180–360°F) hotter than the far side. This temperature difference may still be maintained by the decay of radioactive elements.

“The disparities in surface elevation, crustal thickness, and internal heat content between the near and far sides confirm this internal asymmetry,” Park added.

With a diameter of approximately 3,475 km (2,160 miles), the moon’s mantle—comprising about 80% of its mass and volume—is located 35–1,400 km (22–870 miles) beneath the surface and is made up primarily of olivine and pyroxene, minerals also found in Earth’s mantle.

Alex Berne, a computational planetary scientist at Caltech and study co-author, noted: “The alignment between mantle asymmetry and surface geology—like the distribution of volcanic rocks—suggests that the ancient volcanic processes are still influencing the moon’s interior today.”

The GRAIL mission, using twin spacecraft named Ebb and Flow, orbited the moon from December 2011 to December 2012. The mission produced the most accurate lunar gravity map to date.

“This refined gravity map lays the groundwork for lunar Positioning, Navigation and Timing systems,” Park explained. “Such systems will be critical for the safety and accuracy of future lunar missions, providing a dependable reference for time and location.”

Researchers believe this method of studying planetary interiors through gravity could be applied to other celestial bodies such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Ganymede—both considered promising in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Meanwhile, the new insights help deepen our understanding of the moon’s structure and evolution.

“The moon plays a crucial role in stabilizing Earth’s rotation and in generating tides, which influence many natural systems,” Park said. “Although we’ve made significant discoveries through space missions, much about the moon’s deep interior remains a mystery. As our closest celestial neighbor, it remains a key target for scientific exploration.”