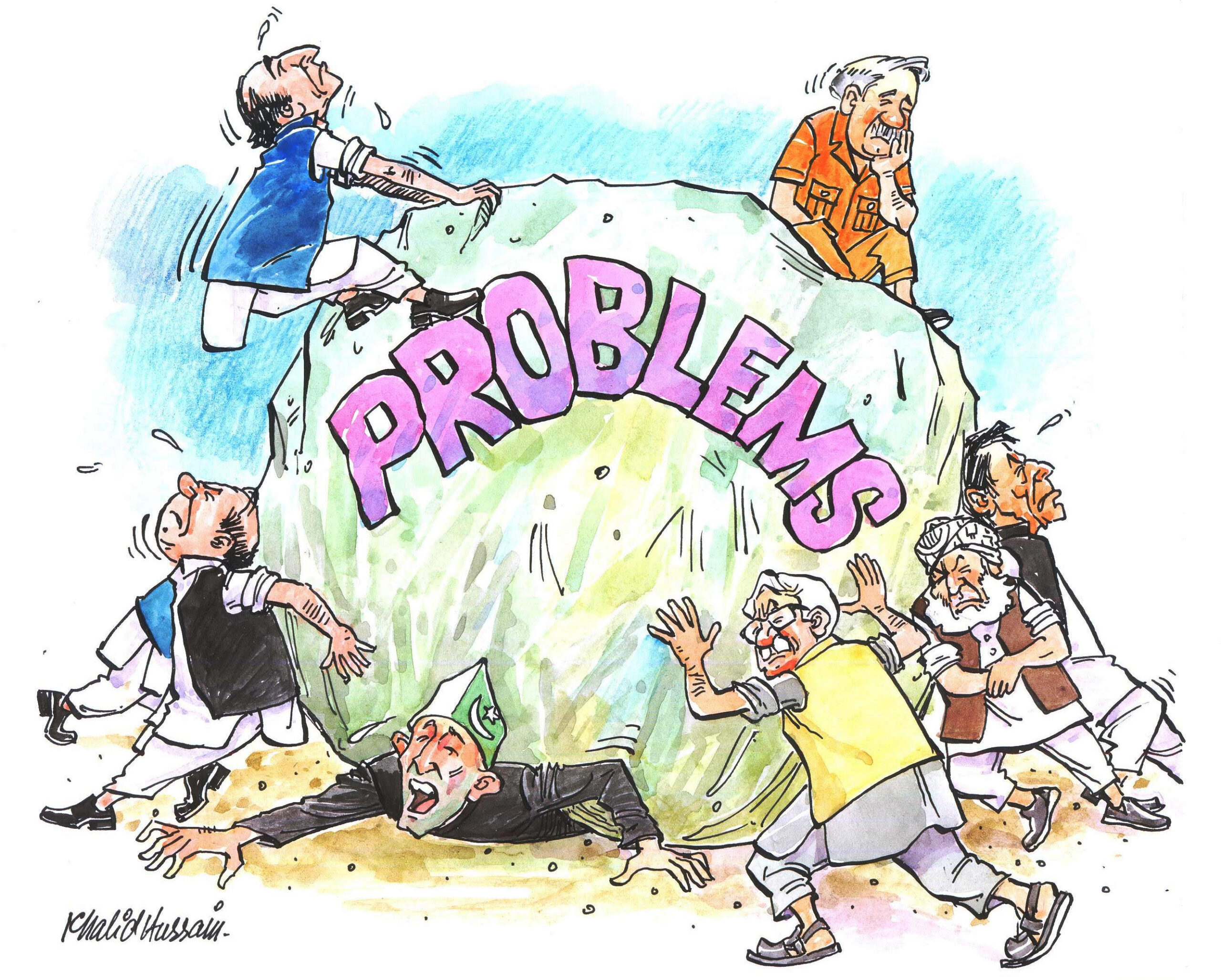

True, apolitical actors have never let go a chance to distort, deface and debase democratic dispensation in the country but can we altogether absolve politicians of the responsibility of a teetering political system? Despite long stints of dictatorships, whenever our politicians got a chance or a half-chance, did they judiciously use the opportunity to strengthen the political system? Or they proved short-sighted collaborators, devoted to self-aggrandizement and selfish, petty gains?

Let’s go to the genesis of it all. The party leading the freedom movement of India, Indian National Congress had a long history of political struggle. It had among its ranks seasoned politicians, imbued with the spirit of nationalism, resisting the colonial power and suffering for their defiance of the Raj. The Congress party existed at the grassroots level and its leaders hailed from various walks of life, including urban middle classes. On the other hand, All India Muslim League was a much younger party, and its leadership was largely restricted to the upper classes, nawabs and sardars. It was around 1940 that the League turned towards peoples’ politics, while the 1946 elections were perhaps the first serious sign of its popularity among the Muslim masses. Interestingly, most of the senior leadership of the League came from the Uttar Pardesh or other Indian states that were not going to form a part of the new Muslim state. In a word, the League politicians were less rooted, and less experienced at the statecraft.

Little wonder then that Pakistan could not have its first constitution for about nine years while India had its first constitution ratified by its constituent assembly in 1949. Ironically, Pakistan’s constitution was abrogated in 1958, within about 2 and a half years, by the first tinpot dictator General Ayub Khan. Likewise, India had its first general elections in 1951, while Pakistan had to wait for about 23 years after its inception for its first general elections.

Obviously, Martial Laws are primarily responsible for the weakening of the political system in the country, and from the word go Ayub Khan was taking interest in politics, which earned him scolding and punishment (of unfavourable posting to East Pakistan) from Jinnah himself. Another General, Akbar Khan, allegedly planned an attempted coup in 1951 against the Liaqat Ali Khan government, known as the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case. Apolitical elements have been trying to assume a political role, to capture more and more resources of the land, right from the inception of the country. But even in the first couple of years of the governance, there were no great examples set by the politicians in-charge.

Federation is a rather delicate political arrangement that requires justice, rule of law, equality among the federating units, and, at times, magnanimity on the part of the big brother. These principles, unfortunately, were flouted straightaway. For instance, the principle applied to all the provincial governments in 1947 was denied to the then NWFP government of Dr Khan sahib, which was dissolved within a week of Independence. Bengalis were denied their language, as Urdu was declared as the sole national language. Against the wishes of Sindhi Nationalists, after partition Karachi became the federal capital, and the provincial capital was moved to Hydrabad – an administrative decision that hugely impacted the future of relations between Sindhis and non-Sindhis.

least, a chequered history in the country. Later, the martial law dictators and rogue elements in certain institutions played havoc with our electoral system, but even in the earlier years, when politicians were more in control, the precedents were wicked. The term ‘Jhurloo’ was

coined to describe the first election held in Punjab after partition in March 1951. It was a bad beginning. In 1954, when the first election was held in East Pakistan and the Jugtoo Front formed the government, it lasted a couple of months before its dissolution by the federal government on charges of ‘treason’.

Firm, principled party affiliation is another prerequisite for strengthening political systems. Pakistani politicians failed on that count, to start with. In 1953, when prime minister Khwaja Nazimuddin was removed by Governor General Ghulam Muhammad, the next day almost the entire party had ditched him. Many League leaders didn’t think twice in 1955, abandoning the League to be a part of a new political party, Republican, formed at the behest of the Governor General Iskandar Mirza and the military establishment.

In October 1958, when the government had planned to hold the first general elections in the country, the first martial law was imposed in the country – perhaps the darkest hour of the country’s history. Many influential politicians, particularly from the West Pakistan, supported the dictator, Ayub Khan.

Ayub Khan brought into being a constitution in 1962, which was aptly described as a ‘constitution of the president, by the president, for the president’. Ayub had to his ‘credit’, the first presidential election based on the system of basic democracies (local bodies) that served as an electoral college for the election. Madir-e-Millat Fatima Jinnah was defeated in that rigged presidential election, and with it died the last ray of hope, particularly for the East Pakistanis, of ever having a fair political system in the country that could ensure them equality vis a vis the West Pakistan.

No one expects the martial law dictators to bolster democratic political systems, as in strong political systems all institutions function within an ambit defined by the constitution of the land, ensuring just distribution of resources among institutions, federating units and citizens at large. But when after 13 years of dictatorial rule, the country was dismembering, the role of West Pakistani politicians was far from just and honourable. There were hardly any sane voices, protesting the March military action in East Pakistan. Even Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto made the following comment on the Operation Searchlight: “Thank God, the country has been saved.”

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s rule was a mixed bag, but as for strengthening the political system, his record looked rather dismal. ZAB put his political opponents behind bars, dissolved his opponents’ governments of NWFP (now KPK) and Balochistan, approved of military action in Balochistan, and finally held a controversial general election. Even his party members suffered his wrath every now and then, facing jails or physical torture. Five and a half years after the dismemberment of Pakistan, another martial law was imposed in the country. Military dictator Ziaul Haq’s sins were numerous. He arranged ZAB’s judicial murder, destroyed the political parties, held partyless polls, promoting parochial culture, dividing the society on the basis of cast and creed. He used the religion card to perpetuate his illegitimate rule for 11 years.

Politicians, after Zia, got another opportunity, though under the strict watch of the establishment, but it was squandered as Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto served two terms each as prime minster, collaborating with the powers that be to dislodge each other from power. They tried to decimate each other through false cases. In 1999, yet another martial law was imposed by General Pervez Musharraf. The sordid tale of undermining the political system continued unabated as

Musharraf like the previous martial law dictators weakened the political parties on purpose, and created a King’s party.

Many believe that the biggest achievement of main political parties, PML-N and PPP, in the entire political history of the country was the Charter of Democracy signed by Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif that led to the 18th amendment, cleaning up the 1973 constitution of all the tinkering done with it by the martial law regimes. This agreement on the political roadmap was a humungous victory of the political forces. Later, there have been certain violations of the Charter by the two parties; however, the 18th amendment remains the high water mark of our recent political history. Meanwhile, a new political party emerged on the horizon and introduced a new, populist brand of politics wherein every politician of note outside its pale was dubbed corrupt and jailed or proceeded against. Every dissenting voice from judiciary, media or other institutions like Election Commission, is either silenced or threatened to be mummed. The present ‘hybrid’ system apart, Imran Khan is a politician, and his failures of governance will be considered a failure of politicians in general. After all, he is the chief of one of the two most popular political parties of the country.

All said, political parties need to respect and strengthen Parliament against all odds. With Nawaz Sharif as PM attending 15 percent of the NA sittings and PM Imran Khan with 10 percent, have disappointed many. Political parties need to have more democracy within, ensuring fair internal elections, and more open policy debates. It is certainly time to sign a new ‘contract’ by all the actors of political arena, including apolitical ones, vowing to honour the constitution, as that is the only path to guarantee the strengthening of our political system.