COVID-19 disrupted the rhythm of everyday life—factories once booming, market places hustling -bustling , and rickshaws earning wages door to door all fell into the void of the pandemic. This void gobbled away not just the hustle and bustle of everyday life, but also the modest, steady incomes that much of the population relied on—millions depended on them to feed their little children, keep a roof over their heads, and sustain the basic necessities of life. Many families’ survival was standing on the frailest margins—one unpaid bill or the closure of a workplace would strip them of their basic necessities, leaving them with nothing but fear and uncertainty. The Islamabad Policy Research Institute’s report, “The Emergence of the ‘New Poor’ in Pakistan,” authored by Dr. Aneel Salman and Maryam Ayub, shows how those everyday rhythms were the real shock absorbers of poverty—and how, when they vanished, people who had once lived with dignity found themselves suddenly and painfully exposed.

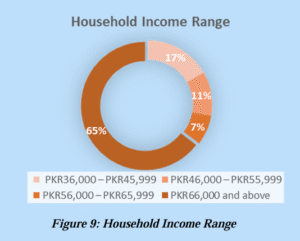

According to estimates, by 2019 the national poverty rate in Pakistan was projected to fall by 8.2%, but the pandemic gave a serious blow to this optimism. Moreover, it proved to be a fertile breeding ground for new poverty, but it was not the kind that depicted the picture of rural destitution. This time the picture was grimmer, as poverty had seeped into urban life as well. It included workers from manufacturing industries (26%), construction (20%), transport and storage (17%), wholesale and retail trade (16%), community, social and personal services (11%), and agriculture, forestry, and fishing (5%). The income of daily wage earners plummeted by 64%. These wage earners were mostly employed in the manufacturing, construction, and transportation sectors.

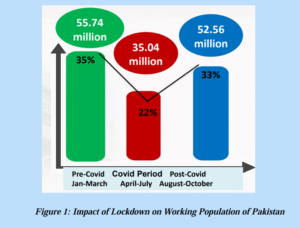

The data is staggering. The study estimates that almost 20 million people in Pakistan slid below the poverty line during the height of the pandemic, effectively erasing a decade of progress in poverty alleviation. Employment figures, too, illustrate this freefall. In 2020 alone, an estimated 27% of the workforce reported reduced hours or complete job loss. In urban centres like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, service-sector workers—from shop assistants to waiters to private school teachers—were among the hardest hit. Their plight was compounded by the fact that many were in the informal economy, excluded from state-backed social protection programs.

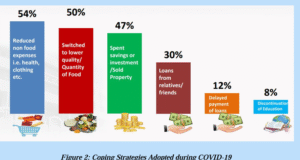

But statistics only partially capture the human cost. Families that once managed household budgets with precision suddenly found themselves choosing between rent and food. Mothers reported cutting down on their own meals to feed their children. According to Dr.Salman and Maryam Ayub, the proportion of households reducing food consumption surged by over 30% during the early months of the crisis. Malnutrition, that was and is a highlighted issue for Pakistan, intensified during this pandemic. Moreover, for school-going children the loss was spread in every plethora of life; it was not just limited to malnutrition. It created a void in their education, and affordability of online education was a privilege not extended to all, which meant millions risked never returning to education, in lieu endangering their long-term earning potential.

Healthcare was another silent victim. The study notes that nearly 40% of households delayed or avoided medical treatment during the pandemic due to income shocks. What began as a medical concern spiralled into something far greater. Vulnerable families were not only stripped away from health but also from financial help and dignity. A single misfortune had the power to unravel the struggle of years into despair overnight. This was the cruel hallmark of the new poor. Erosion of resilience of once-stable households seemed to be the defining feature of this pandemic. Their position had been made so fragile that one unexpected crisis—an illness, loss in job, or a sudden expense—was sufficient enough to topple over their stability, leaving them nothing to lean on. Meaning they were those affectees who didn’t inherit poverty, but it came into their lives as a spillover effect.

The study limns how social cohesion began to fray, as families started to depend on family, friends, or community leaders—people who themselves had money only sufficient to meet their own needs. Inevitably, the sense of security that many households had built broke, leaving nothing but empty pockets and dampened spirits. Poverty was no longer something measured merely in incomes and expenses; it became a lived reality of lost choices and shattered dreams. Parents watched the bright possibilities of their children’s future shrink before their very eyes. This was the pain the new poor had to endure—witnessing all the hard work of previous years become suddenly redundant.

What makes the scenario worse is the lack of responses. Pakistan’s flagship Ehsaas program did expand its cash transfers during COVID-19, reaching approximately 15 million families.What’s worse was the safety nets that existed then and even now—BISP, PPAF (Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund), Ehsaas Kafaalat, Rozgar Scheme, etc.—were ill-suited for the fallen. These programs were built to serve individuals earning less than Rs.25,000 or those who did not own a car, i.e. the chronically poor; hence, they failed to integrate and recognize households that had recently become poor, especially in the urban areas. Poor administration, exclusive rules of eligibility, and specific targeting left many newly destitute families unrecognized and helpless. The pandemic required policymakers to provide not routine paperwork or delayed assistance, but urgent relief. The demand was sudden and vast, calling for flexibility and immediacy that the rigid bureaucratic machinery could not provide. The consequences extended beyond economics.

Dr. Aneel Salman and Maryam Ayub recommend that policies be humanized, implemented, and garnered by policymakers—policies that are people-centric, not form-centric. Social protection, everyone agrees, needs to be flexible and fast. That means building systems with automatic stabilizers and rapid-response cash transfers that can expand quickly in times of crisis. In order to make social protection’s tree bloom, it is important that the rigid eligibility rules are loosened so that families who have recently slipped into poverty—particularly in urban areas—can receive help without being trapped in bureaucratic delays. Job security is equally critical, as protecting employment prevents temporary setbacks from turning into permanent unemployment. Wage subsidies, urban public-works projects, and targeted support for micro enterprises can keep workers connected with the labour market, according to Dr. Aneel Salman and Maryam Ayub. At the same time, essential services must be safeguarded: subsidies for free or low-cost primary healthcare and measures that keep children in school are vital to sustaining the future earning power of an entire generation.

Data and monitoring are not just dry, technical tools—when crises strike, they are the invisible glue that holds credible responses together. Without these tools, it becomes nearly impossible for governments to track those who are barely surviving and those who have already fallen through the cleft created by COVID-19. Dr. Aneel Salman and Maryam Ayub’s research underscores this reality by using urban survey data and regression analysis to reveal patterns of vulnerability that might otherwise remain hidden. It shows that policymakers can anticipate which households are likely to suffer or become at risk in times of crisis. But this is only possible if they are willing to invest in systems that gather solid data from the labour market, track fluctuations in income with precision, and maintain integrated provincial databases that speak to one another.

Importantly, these suggestions are not charity in the abstract; they are investments in resilience. Protecting children from nutritional deficits, ensuring uninterrupted education and preventing households from falling into high-interest debt save money over the long run. Pilot programs — carefully designed and rigorously evaluated — can test innovations like time-limited UBI pilots for students and informal workers, shock-indexed transfers, or urban UBS (Universal Basic Services) packages. If pilots work, they can scale. If they don’t, we learn quickly without entrenching ineffective programs.

In essence, the pandemic carved out a dual Pakistan: one where the already poor slipped deeper into deprivation, and another where families who once managed to stand on their own feet suddenly found themselves tumbling into poverty’s grip. These “new poor” are not just numbers on a chart — they are shopkeepers whose shutters never rose again, seamstresses whose orders vanished overnight, and children who watched their classrooms turn into unreachable screens. What began as a temporary disruption has hardened into a long-term challenge.

Dr. Aneel Salman and Maryam Ayub warn that unless Pakistan acts deliberately — by widening social protection to include informal workers, investing in digital education for children stranded on the wrong side of the digital divide, and cushioning small enterprises against repeated shocks — this fragile class may become permanently trapped in the cycle of want.

The rise of the new poor is a painful reminder that poverty is never still. It bends and twists, widening its grip whenever crisis strikes, often pulling under those who only yesterday seemed safe. Pakistan must realize it now stands at a crossroads — a now-or-never moment. The victims of COVID-19 are more than facts and figures; they are people who once dared to dream of dignified lives, but whose dreams were ripped apart, leaving them with nothing but uncertainty. For Pakistan, the urgency could not be greater than it is now. These invisible casualties must be empathized with — parents who were once moving toward mobility, and children who had envisioned their futures but now bear the weight of instability. It is the need of the hour to implement bold, people-centered policies, because if the challenge of the new poor is not addressed, today’s hardships may solidify into generational chains of poverty, erasing fragile progress and clouding futures that once seemed promising.

About the Authors

Dr Aneel Salman holds the distinguished OGDCL-IPRI Chair of Economic Security at the

Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) in Pakistan. As a leading international economist, Dr

Salman specialises in Monetary Resilience, Macroeconomics, Behavioural Economics,

Transnational Trade Dynamics, Strategy-driven Policy Formulation, and the multifaceted

challenges of Climate Change. His high-impact research has been widely recognised and adopted,

influencing strategic planning and policymaking across various sectors and organisations in

Pakistan. Beyond his academic prowess, Dr Salman is a Master Trainer, having imparted his

expertise to bureaucrats, Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs), military personnel, diplomats, and

other key stakeholders furthering the cause of informed economic decision-making and resilience.

Maryam Ayub holds an M-Phil in Economics and Finance from PIDE. Her areas of expertise are

Macroeconomics, Climate Finance and Development Economics.