Watching a revolution is like watching a hurricane. At the end, you get either a rainbow or a flood. For Ayatollah Khomeini and other Islamists, the seventies ended with a rainbow. For the United States, however, Iran is still flooded 42 years after the Revolution that rocked the world on 11 February 1979. Its trademark chants of “Death to Israel, Death to America” still reverberate in Iran.

The seventies started with the death of President Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt. From French West Sahara to Egypt to Syria, from India to Indochina, the majority of Third World countries were coming under socialist influence.

To get an idea of what the seventies must have felt like, consider this: The World was hit by the Yom Kippur Arab-Is- raeli war in 1973, followed by the Arab oil embargo, the 1975 American defeat in Vietnam, the 1977 takeover by Pakistan Army deposing PM Z A Bhutto, the Egypt-Israel peace accord in 1978, and the Russian takeover of Afghanistan in 1979.

At the outset of that eventful decade in 1971, one person, Iran’s Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, attracted the world leaders by celebrating his Western style monarchy as a legacy of 2,500 years of Persian Empire.

Through his decade-long White Revolution, started in early sixties, he westernized the Iranians by pushing back traditional and religious lifestyles, introducing female voting rights, marginalizing clergy, and rapid industrialization.

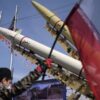

Enriched by oil money after 1973, Iran embarked upon arming its defense forces with the latest weaponry and advanced military training from the US and Israel. The Shah of Iran was eying to become a mini-superpower of Middle East and Asia, a deterrent against Soviet Russia and its Socialist Arab neighbors.

But Alas! On 16 January 1979, under pressure and on the run from the Ayatollahs, the Shah left Iran with tears in his eyes. How could this happen, especially when Tehran housed Asia’s CIA headquarters? Let’s glance through the early history of Shah’s ‘modern’ Iran for clues.

In the backdrop of Anglo-Russian direct control of north and south regions of Iran, Colonel Reza Khan, Head of the Persian Cossack Brigade overthrew the last Qajar King in 1921 and made Sayyid Zia Al-Din Tabataba’i the Prime Minister. Under pressure from clergy, Reza Khan abandoned the idea of Kemal Ataturk style republic and declared himself the king and founded the Pahlavi dynasty (1925-79). British companies had already discovered oil in southwest Iran in 1908. They kept most of the revenue and secured extraordinary legal immunity for themselves. After becoming the king, Reza Shah (previously Khan) introduced secular courts overseen by state bureaucracies and banned the custom of women wearing veils. He forced modernization and westernization and marginalized the clergy. He renegotiated British oil concessions and in the 1930s expanded trade with Germany to counter the threat of Anglo-Soviet military takeover. After an Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941, his refusal to severe ties with Germans resulted in his abdication in favour of his 21-year-old son Muhammad Reza Pahlavi.

Young Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was viewed as a puppet of Western powers. In 1951 Nationalist parliamentarian Dr Muham- mad Mosaddeq and parliament forced the Shah to nationalize Imperial Iranian Oil Company (British Petroleum PLC). The British company left Iran causing fall in oil revenues.

Under pressure from Britain and America, Shah tried to reverse the decision. A power struggle ensued and in 1953 the Shah escaped from Iran after being defeated by the Dr Mosaddeq, the massively popular prime minister. Backed by CIA and MI6, pro-royal elements brought back the Shah, tried the PM for treason and kept him under house arrest till his death in 1967.

The Shah maintained close relationship with the United States, both regimes sharing a fear of the southward expansion of the Soviet Union. Leftist and Islamist group attacked his government (often from outside Iran as they were suppressed within) for violat- ing the Iranian constitution, political corruption and political oppression by the SAVAK (Secret Police).

Shia ulema have historically had significant influence in Iran. Among the Twelver Imamia Shia of Iran having a Marja-e-Taqlid (a supreme Legal Authority or the source of emulation) is obligato- ry for every practicing Shia. Besides religious guidance, functions of Marja-e-Taqlid is the collection of Zakat (1/40 of Income) and Khums (1/5 of Income). There are several marjas at any given time.

Thus, the Shia ulema of Iran were a source of financial support for the needy and had close links with the Bazaaris (Traders). Ulema also held large tracts of land through Waqf (Trust Property).

In 1891, a fatwa by Ayatollah Sherazi led to a Tobacco boycott and the ensuing public protest effectively destroyed an unpopular concession granted by the Shah giving a British company monopo- ly over buying and selling Tobacco in Iran. Then during the 1905-1911 the Qajar King had to introduce constitutional reforms, again pushed forward by ulema.

Ayatollah Ruhullah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian revolution first came to political prominence in 1963 when he led opposition to the Shah and his program of reforms known as the “White Revolution” which aimed to break up land holdings (even owned by ulema) for distribution among landless farmers, allow women to vote and religious minorities to hold office, and finally grant women legal equality in marital dealings.

Khomeini declared that the Shah had “embarked on the destruction of Islam in Iran” and publicly denounced the Shah as a “wretched miserable” man. Following Khomeini’s arrest on 5 June 1963, three days of major riots erupted throughout Iran, with Khomeini’s supporters claiming 15,000 killed by police.

After eight months of house arrest, Khomeini was release but he continued his agitation against the Shah condemning Iran’s relations with Israel and its “capitulations” to the US. In November 1964 he was re-arrested and sent into exile, where he remained for 14 years until the revolution in 1979.

Despite political repression the budding Islamic revival spearhead- ed by Khomeini began to undermine the idea of Westernization as progress that was the basis of the Shah’s secular regime. Jalal Al-e-Ahmad’s idea of Gharbzadegi – that Western culture was a plague or an intoxication to be eliminated took hold – as did Ali Shariati’s vision of Islam as the one true liberator of the Third World from oppressive colonialism, neo-colonialism and capital- ism; and Ayatollah Motahhiri’s popularized retelling of the Shia faith all spread and gained listeners, readers and supporters.

Most importantly, Ayatollah Khomeini preached that revolt, and especially martyrdom against injustice and tyranny was part of Shia Islam, and that Muslims should reject the influence of both capital- ism and communism which the slogan “Neither East, Nor West – Islamic Republic”.

To replace the Shah’s regime Ayatollah Khomeini introduced the ideology of Velayat-e-Faqih (Guardianship of the Jurist) as Govern- ment, postulating that Muslims required “guardianship” in the form of rule by the leading Islamic Jurist or Jurists.

Such rule would protect Islam from deviation from Sharia Law, and in so doing eliminate poverty, injustice, and the plundering of Muslim lands by foreign unbelievers. And this duty could be performed while waiting for the Imam Ghaeb (imam in Occulta- tion) thus removing the lacuna of Shia fiqh for legitimacy to rule in the absence of Imam Ghaeb.

Publicly, Ayatollah Khomeini focused more on socioeconomic problems of the Shah’s regime (corruption, unequal income, and development issues). Khomeini’s book on Velayat-e-Faqih was widely distributed among students, ulema and the business commu- nity. A powerful and efficient network of opposition began to develop inside Iran, employing mosques sermons and smuggling audiocassettes of recorded speeches by Khomeini, among other means.

Beside Khomeini’s followers, in the cities and educational institu- tions secular leftist and Islamic modernist students as well as guerrilla groups rendered great sacrifices. Young educated males and females were abducted from such institutions to unspecified locations and for indefinite periods. But they spearheaded the resistance in cities.

The leftist guerrilla groups (e.g. Fedayeen-e-Khalq), as well as Islamic socialists (Mujahedeen-e-Khalq), unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the regime of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi from 1971 to 1979. Yet during the final days of the revolution, they delivered the regime a coup de grace in street fighting. The militancy training these groups had received from PLO camps in Lebanon came in handy at this juncture.

Constitutionalists wanted the Iranian constitution of 1906 to be restored. Prominent in it was Mehdi Bazargan and his liberal, moderate Islamic group Freedom Movement and the more secular National Front. Very notable theologian Ayatollah Sayyid Mahmoud Taleghani leading these parties favoured rationality in Islam and also supported Dr Ali Shariati’s teachings. Tudeh Party’s communist followers along with leftist guerrillas of Fedayeen-e-Khalq were severely suppressed by Shah’s security forces. The Islamist group that prevailed ultimately contained the core supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini.

Democrat Jimmy Carter was sworn in as the 39th President of the US on 20 January 1977. He urged Shah to allow more democratic freedom in Iran. This infused the Anti-Shah movement with new vigour. In January 1978, former PM Amir Abbas Hoveyda wrote a derogatory article against Khomeini in an official newspaper labelling him a British agent.

The backlash was swift and spectacular. Riots erupted all over Iran and several lives were lost when security forces opened fire on demonstrators. Forty days later, chehlum (40th Day mourning) procession in honour of the martyrs resulted in more bloodshed.

Violence snowballed as this cycle of Chelum attracted more crowed and the authorities continued with their murderous ways throughout spring and summer of 1977. In September that year, strikes by industrial workers, especially, National Iranian Oil Company further paralyzed the nation.

On 8 September, the Shah declared Marshall Law. Unaware of the development, a huge crowd gathered for a demonstration in Tehran’s Jaleh Square. Security forces opened fire. The death toll was anywhere between 88 and 15,000 depending upon whose version of events you believe. In November, the Shah appointed General Azhari as PM.

To appease the public, the Shah released 1,000 political prisoners on his birthday and arrested former ministers but nothing could stop the avalanche of revolutionaries, since they knew that no retaliation would happen if they participated in demonstrations.

In December 1978, the Ashura gathering of millions in Tehran became a pro-Khomeini demonstration. Now Shah was advised by his close confidants to appoint a new Prime Minister. He appointed Shahpour Bakhtiar, a follower of Dr Musaddeq as PM, who took oath only on the condition that Shah would leave the country.

In January 1979 leaders from the US, Britain, France and Germany in an already scheduled meeting came to the consensus that the new government in Iran would be pro-west and not communist. Giscard d’Estaing, the French President conveyed a message from Jimmy Carter to Khomeini (Staying in France after expulsion from Iraq) that if he supports PM Shahpour Baktiar’s government, America would ensure Shah leaves Iran. Khomeini responded by saying Shahpour Bakhtiar’s government was illegitimate and Iran should be left alone.

On 16 January 1979, Shah left Iran for holidays hoping to return soon, but he was not optimistic. The next day the whole Iran was jubilant but the country descended into lawlessness during the next few days.

To fill the political vacuum created by the Shah’s departure, Ayatol- lah Khomeini returned to Iran on 1 February 1979 after fifteen years in exile. He was greeted by millions of Iranians from the airport to his place of residence.

Khomeini appointed Mehdi Bazargan as his prime minister, declin- ing to recognize the sitting prime minister Shahpour Bakhtiar.

On 11 February 1979, the Iranian Air Force declared its neutrality between the sitting government of the Shah-appointed prime minis- ter Shahpour Bakhtiar and Mehdi Bazargan, the prime minister appointed by Khomeini. The revolutionaries took charge of the administration, police and all state institutions.

Thus arrived the Islamic Revolution in Iran.