Germany’s small hospitals are disappearing:

Germany’s small hospitals are disappearing

One small hospital closes every month in Germany. Politicians say there are too many, and the health care system can’t afford to keep them all open. But their critics say patients may die due to closures.

Daniela Thiesen is fighting for the hospital in her small hometown of Adenau, in western Germany. Despite the freezing temperatures, she has taken to the street to protest against the planned closure of the city’s only hospital, the St. Josef Clinic, scheduled for the end of March 2023.

“We also need good clinics in the countryside, not second-class care,” said Thiesen, who is involved in the citizens’ initiative for health care in the town of 3,000 inhabitants.

The surgical department in Adenau closed three years ago. There are currently just 74 beds and departments for acute geriatrics, internal medicine, radiology and outpatient surgery. St. Josef Clinic, set up by Franciscan nuns in 1863, is making losses and doesn’t even have enough staff to care for the dwindling number of patients.

Thiesen has many stories to tell, like the one about a stroke patient who had to be driven 150 kilometers (93 miles) to a hospital in the state capital, Mainz, because there was no nearby clinic. Or the elderly lady who had to wait three hours for an ambulance to arrive at her house, although she was in severe pain.

“I can see the elementary school from my house, and three weeks ago a child had an accident there and an emergency helicopter had to come from Luxembourg to fly it to a hospital in Trier, 100 kilometers away. We’re not third-class people here, we’re legally entitled to standard care,” she told DW

Thiesen’s anger is directed toward politicians and the operator of the local hospital. The Catholic social enterprise operates the Marienhaus Group of hospitals across three federal states, including homes for the elderly and a handful of hospices and youth welfare facilities.

Marienhaus spokesman Dietmar Bochert, who has the thankless task of defending the closure of the St. Josef Clinic, said things have changed. “Patients nowadays head straight to the big clinics or the specialists instead of the local hospital,” he said.

Only 20 of the 74 beds have been occupied in recent years at any given time — mainly the ones in the geriatric ward. In 2019, only five life-threatening emergencies were treated at St. Josef Clinic, and the ambulance has for years been heading directly to other clinics. The hospital’s total deficit now stands at €10 million ($10.6 million).

And this year the clinic was dealt a deathly blow. “The Association of Health Insurance Funds, the Association of Private Health Insurers and the German Hospital Association recognized the lack of demand in Adenau and took the clinic off the list of the hospitals with a claim to security benefits,” said Bochert.

In other words, the clinic was no longer considered indispensable — a status it still held until the end of 2021. Bochert is in the process of finding new jobs for the 55 full-time employees. The fact that St. Josef has no future is mainly due to the situation in the countryside. Even company e-bikes and a good pension scheme are often not enough to lure in new staff.

“We’re on all social media and recently even started various advertising campaigns to find employees,” he said. “In one case where we were looking for a senior physician — we couldn’t convince anyone, even though we approached 100 candidates via headhunters. But, at the end of the day, recruitment always fails when you say the job’s in Adenau. Then you quickly get told ‘no, thank you.

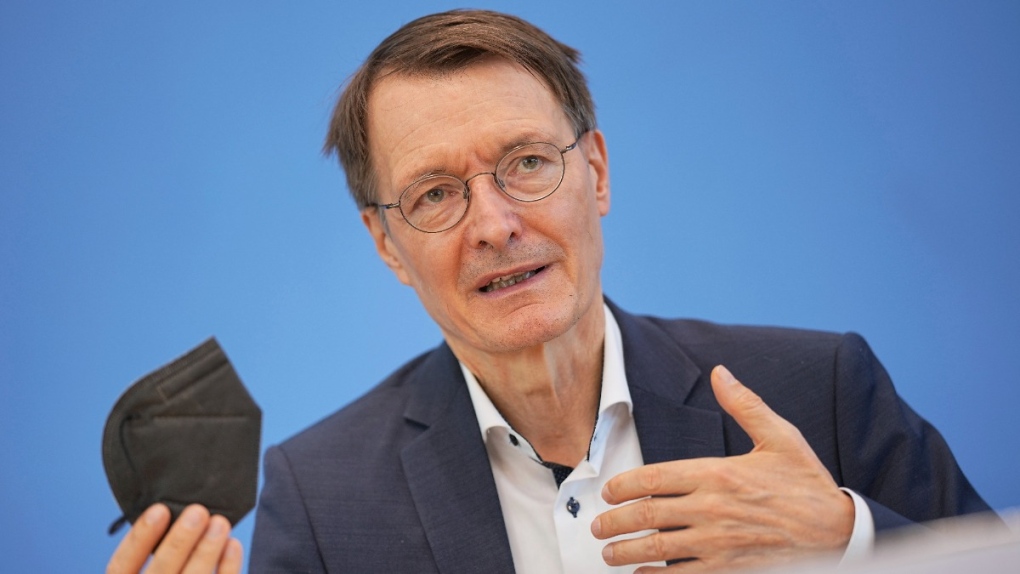

Health Minister Karl Lauterbach is planning a major hospital reform which he calls “a revolution.” The plan is to have a three-tier hospital system.

Level 1 are clinics that offer basic care — some of them may have a well-equipped emergency room. Level 2 consists of hospitals offering standard and specialized care. Level 3 are hospitals with a wide range of specialized care, such as large university hospitals. And there will be specifications for equipment, patients’ rooms, and the number and qualification of personnel for each category.

Klaus Emmerich is upset by these plans. In the Bavarian town of Sulzbach-Rosenberg, which has a population of 20,000, he was on the board of directors for the local hospital.

“If the next hospital ends up being more than a 30-minute drive away, then that’s dangerous and can be life-threatening for individual patients.”

According to his calculations, 650 hospitals in Germany are in danger of becoming no more than glorified nursing homes. Germany’s Health Ministry envisages that such basic clinics could be managed by qualified nursing staff instead of doctors. There are also plans to increase outpatient care, that is, via doctors in private practices, and transfer patients to level 2 or level 3 hospitals only in the case of emergencies.

To Emmerich, this amounts to “sheer mockery to speak of ‘hospitals’ when there is no more than glorified short-term or outpatient care. We will end up with many regions in rural areas with inadequate medical treatment.” He said “second rate” means no more 24-hour medical availability, no inpatient emergency room with a trauma room for resuscitation, and no more computed tomography.

Reinhard Busse, a professor of health care management at the Technical University of Berlin, has a completely different view and rejects the idea of keeping as many clinics as possible open, and then equipping them with minimum standards.

Busse believes in the “less is more” approach, and thinks that no clinic is better than a bad clinic. “We have too many hospitals in Germany. Some districts have three smaller hospitals, all of which are poorly equipped. Instead of three bad hospitals, it’s better to have one good hospital.

Busse is also one of the 17 scientists and physicians who lashed out at Lauterbach’s talk of revolution. With €466 billion ($495 billion) in health expenditure last year, Germany is able to afford one of the most expensive systems in the world. Only the United States spends a larger share of its gross domestic product on health care. So there’s no lack of money, said Busse — it’s just badly distributed.

“Hospitals are absorbing more and more doctors like a sponge, which partly explains the lack of resident doctors. We also have a lot of nursing staff compared to other countries. But since we have so many more beds and so many more inpatients, we’ve ended up with a relatively bad nurse-to-patient ratio because we distribute resources so widely.”

Germany has 425 hospitals that would fall into the new level 2 and 3 categories, said Busse. “They are the backbone of care,” he added, arguing that they should be the focus of a reform he believes is long overdue.

“Seventy percent of patients with pancreatic cancer in Germany are not treated in cancer centers, but in hospitals without any specialization,” said Busse. This makes no sense to him. “We now want to introduce the logical principle that hospitals should only treat cases if they have relevant expertise in that particular area.”

Courtesy: This article was originally written in German. The translated version by Oliver Pieper is taken from DW.