Before the advent of ChatGPT, writing was — let’s say — sacred. It was original. Hours and hours of thought and consideration, not to mention the tireless and never-ending editing — all to produce one epic piece of writing. But the end result was totally worth it, as it was something created from the flow of emotions — spontaneous, original.

Ah! Those were the times when individuality was the beauty of art.

Plagiarism was like giving a death sentence to a writer, as there were people learned enough in every field to correct semantics without software.

Enter AI — the evolution, viz-a-viz, a sponge absorbing cognitive abilities.

Recently, MIT Media Lab carried out a study on “The Cognitive Cost of Using LLMs (Large Language Models),” which explored how language models — especially ChatGPT — affect the brain’s ability to think, learn, and retain information.

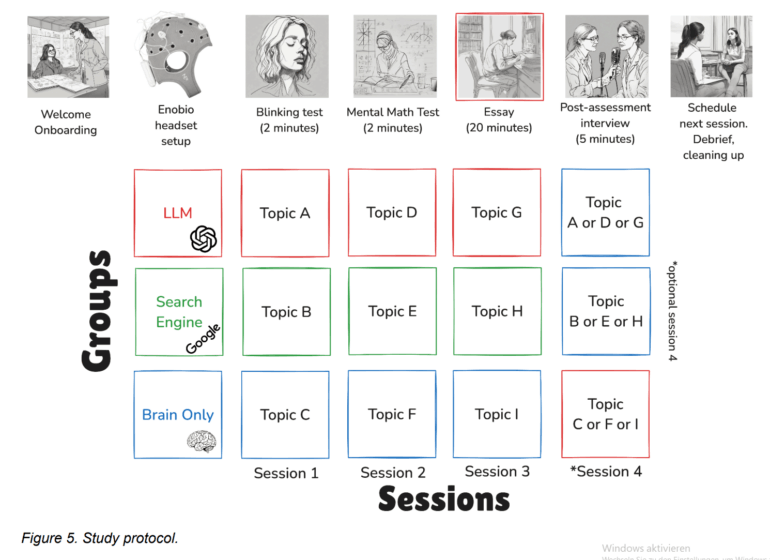

The study comprised 54 participants between the age groups of 18–39. They were further divided into three groups, each consisting of 18 members: ChatGPT, Search Engines, and Brains Only (No Tools). Each group was given three prompts, out of which they had to choose one to write an essay on. The results were to be judged by two English teachers and two AI judges trained by researchers.

It is not surprising, but the English teachers were able to identify the AI-written essays. I mean, who wouldn’t? The monotony of the tone, the lack of individuality, the repetition of ideas constantly weaved in the same way but in different paragraphs, and — not to mention — the rigid writing. The teachers regarded essays written by ChatGPT as “soulless” and claimed that they lacked “personal nuances.”

The brain activity of these participants was measured through EEG. The research established robust evidence that the students who used no tools had a greater sense of satisfaction and brain connectivity compared to the others. Whereas for those who were using AI, it was like their brains had become habitual of crutches. The students were unable to recall their writing or quote things from their text. Moreover, they could not even quote from their essays when asked to recall them by the researchers.

Three sessions with the same group assignment for each participant were conducted. In the fourth, the LLM group participants were asked to use no tools (referred to as LLM-to-Brain), and the Brain-only group participants were asked to use LLM (Brain-to-LLM).

As the level of external help increased, brain connectivity consistently decreased. Participants who relied only on their own thinking — the Brain-only group — showed the most robust and wide-ranging neural activity. Those who used a search engine showed moderate brain engagement. But the group that used a large language model (LLM) like ChatGPT had the weakest overall brain connectivity.

In follow-up interviews, the LLM group also reported the least sense of ownership over the essays they had written. While the Search Engine group felt more connected to their work, it still didn’t compare to the Brain-only group, whose members felt strongly that their writing was truly their own.

When asked to recall or quote from their essays just minutes after writing — in the LLM group — 83.3% struggled significantly recalling what they wrote. In the Search Engine and Brain groups, only 11.1% had difficulty in recalling ideas they had written.

Although using the LLM appeared helpful at first, the results — gathered over four sessions across four months — showed a consistent trend: participants in the LLM group performed worse across every domain we tested, whether it was brain activity, writing quality, or memory.

The Flood of Content, the Drought of Thought

Questions arise after reading this research. The first, basically: since the advent of ChatGPT, the internet has been flooded with all sorts of written content — whether on Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, or Twitter. But the irony is: who is writing all this content, and how much of it is original?

In 2023, the National Endowment for the Arts reported that, over the preceding decade, the proportion of adults who read at least one book a year had fallen from fifty-five percent to forty-eight percent. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, over roughly the same period, the number of thirteen-year-olds who read for fun “almost every day” fell from twenty-seven percent to fourteen percent. So, the number of readers all over the world is decreasing.

When there is a rarity of readers, how can there be an abundance of writers? Or is this what ChatGPT does — give any Tom, Dick, or Harry the chance to be a writer?

Gone are the days when writing was considered sacred, almost akin to a divine revelation — to put it in Wordsworth’s words, “a spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” It was the “real language of men.”

The lack of readers is plummeting; the plight of teachers is increasing. Due to social media, they struggle to get their students to read. And even when they are handed an assignment to write, students return with work that is not merely aided by AI, but often completely written by it.

From Zuckerberg’s Promise to AI’s Shadow

We once were living under the “Zuckerberg Parenthesis” — a time defined by the dominance of social media, particularly platforms like Facebook, where online interaction was driven by human conversation, sharing, and digital community. During this era, theorists imagined the internet as a return to an oral, communal mode of communication.

But now, in hindsight, that idea seems almost outdated — quaint — because we’ve entered a radically different phase, shaped not by people talking to people, but by AI talking back.

With the advent of large language models, chatbots, and virtual personas, online interactions are increasingly generated by artificial intelligence, blurring the boundary between human and machine. These AI systems are trained on vast amounts of written text — almost as if books themselves have awakened — repurposing the very medium (text) that was thought to be fading.

The irony is powerful: just as the written word seemed to be losing ground to casual speech and memes, it reasserts its influence in the form of AI that can mimic human dialogue — reshaping how we value and use language, conversation, and thought in the digital age.

The Vanishing Writer’s Block and the Erosion of Soul

No wonder, rarely anyone goes through writer’s block anymore. (The term “writer’s block” was coined in 1947 by the Austrian psychiatrist Edmund Bergler.) The affliction now known as writer’s block has been recognized throughout history. Writers who are known to have struggled with it include authors F. Scott Fitzgerald and Joseph Mitchell, composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, and songwriter Adele. Another example is Herman Melville, who stopped writing novels a few years after writing Moby-Dick.

When output becomes the only focus, the human emotion that once served as the essence of all forms of creation is discarded — and prompts become the new foundation of creativity. Creativity will not merely decline; it will erode. It will become a thing of the past.

When Greatness Was Human

The intervention of technology has led to a scarcity of innovative writing.

If we look back, has the world produced writers of the likes of Rumi, Iqbal, Shakespeare, or Nietzsche? Writers who had a resounding impact not only in their own times but continue to be quoted across a plethora of fields even today?

Some might beg to differ, claiming that J.K. Rowling and Tolkien are renowned names — but their works, though brilliant, remain specific in scope rather than expanding across vast intellectual and emotional horizons.

What set those earlier literary minds apart was their ability to produce great works independent of external resources. The only knowledge they had was that which they consumed from books and the lived experience they carried within. This made their work authentic and deeply individual.

Now, the pressing question that this moment in time poses to mankind is this: Will critical thinking become the first casualty of convenience — brought on by AI?

As the documentary The Social Dilemma aptly puts it, “If something is free, you are the product.” The product, in this case, is humankind — entirely bridled in mind, body, and soul to artificial intelligence. The risk? That we are left, eventually, “brain dead.”

You know what they say: Earth without art is just “eh.”

If creation without human experience ceases to exist, and all that remains are AI models generating art from pre-existing data — where will the essence of emotion go?

It will vanish.

P.S.

Excuse any earlier mistakes — last I checked, to err is human, and perfection divine… or maybe AI, in today’s world.