This month marks 50 years since the “Black September” 1970 war in Jordan, a fateful episode that would have far-reaching consequences in the Middle East. Pitting the Jordanian monarchy against a coalition of Palestinian militants, this war marked the first occasion of a postcolonial Arab state turning on Arab non-state actors – a pattern that has since often been repeated. It marked the end of some major Arab leaders’ career, the start for other leaders, and saw both Jordanian monarch Hussein bin Talal and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat entrench themselves. Finally, in the violent expulsion of Palestinians from an Arab country, it broke a loose etiquette of at least formal solidarity with the Palestinians by Arab states – one that has significance fifty years later as other Arab monarchies line up to recognize Israel.

Hussein drew on an inner circle of military veterans that represented various strata who shared his concern. They included his own cousin Zaid bin Shaker, Habis Mujalli, Nadhir Rushaid had, and Wasfi Tal. The irony was that they had fought with distinction against Israel. But they saw the Palestinian fighters (known as fidayins) as dangerous adventurers and as a potential “state within a state”.

Confrontationalism came alongside increased clashes with the army during spring 1970 after Hussein’s stop-start attempts to limit fidayins’ activity. Iraq’s Interior Minister Saleh Ammash was twice dispatched to broker a ceasefire, once privately offering Arafat a coup against Hussein – which the fidayin leader declined.

He also declined a surprise offer for the prime ministry by Hussein, who instead appointed two pro-Palestinian officials – Abdul-Munim Rifai and Mashhour Haditha – to the prime ministry and army command respectively. But this proved a token gesture since Hussein and his aides quietly maneuvered in the background on their own. Tension in between Jordan authorities and Palestinian groups had a rude shock in midsummer 1970 when the border war (in between Arabs and Israel) suddenly ended with a ceasefire – accepted by first Egypt and then Jordan – brokered by American foreign minister William Rogers. For Washington, the purpose of this plan was to displace Soviet support for Egypt and become kingmakers on both sides of the Palestine dispute. Thus, while the fidayin unanimously condemned it, it was the Marxist groups who went furthest.

Hussein’s military council emerged from the shadows; he sacked Rifai, replacing him as prime minister with retired general Muhammad Daud, and brought the bedouin general Habis Mujali out of retirement to replace Mashhour Haditha. They were aided not only by Zaid bin Shaker, the king’s cousin but also by Mohammad Ziaul-Haq, a then-unknown but ambitious officer with the Pakistani contingent in Jordan who unilaterally offered his advisory service and thus made his first notable appearance before seizing power at home years later.

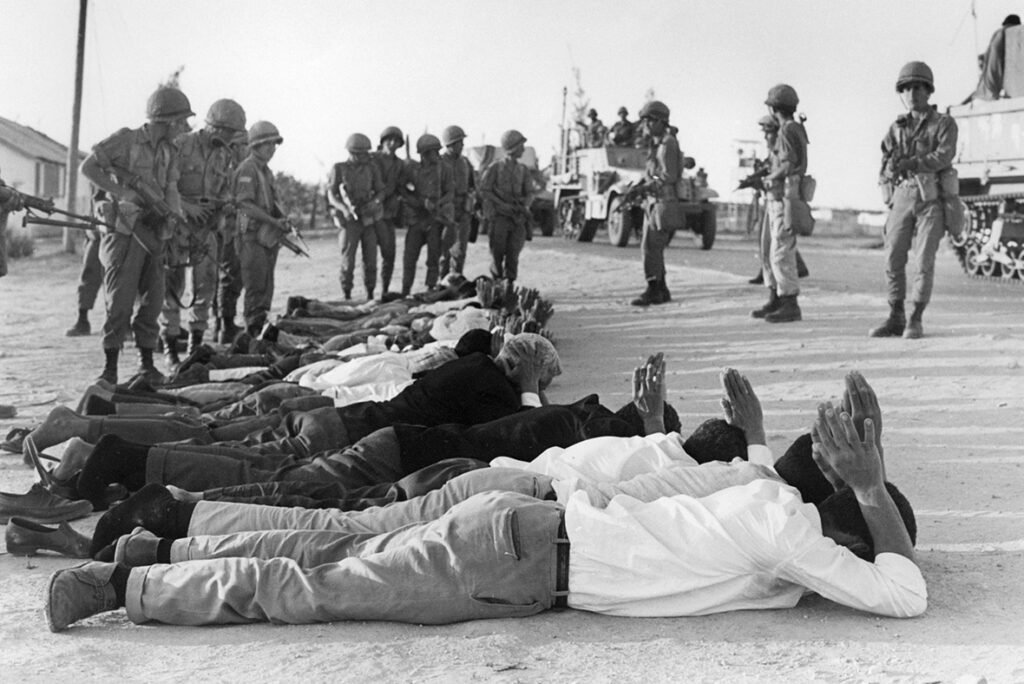

Thousands, both fighters and civilians, were killed in the following days as the army slowly but surely won control of Amman and the refugee camps in the area; among their thousands of captives were Fatah’s prospective “kingmakers” Khalaf and Qaddoumi, belying the pair’s confidence in their ability to unsettle the crown: although many Jordanian soldiers did defect, their number was far less than expected and not enough to tilt events notably.

A bigger concern to Hussein by now was diplomatic action by other Arab states. Hussein soon agreed to a ceasefire, brokered by a dying Gamal Abdel-Nasser, with Arafat in Cairo. “Black September” was over, and its winner was undoubtedly the Jordanian regime.

Aftermath

In spite of the shattering blow to their morale, initial events after September 1970 did not bode particularly badly for the fidayin: they were initially permitted to continue small-scale action against Israel, but under Jordanian surveillance, and the terms of the ceasefire seemed generous enough in the circumstances. There was enough time for the fidayin factions to introspect and attempt to coordinate their forces better, an attempt that largely failed to owe to the mistrust and bitterness that prevailed as they traded blame. But Jordanian state remained cautious.

Black September was a convulsion in the region. It marked Nasser’s last bow; hours after mediating the ceasefire, the Egyptian dictator succumbed to a heart attack. But it had more direct conse- quences in other regional countries: Israel took the opportunity to mop up fidayin bases in the West Bank, while the Baathist regimes of Iraq and Syria were directly convulsed in autumn 1970. Hardan Abdul-Ghaffar, Iraq’s powerful second-in-command, was scape- goated for Baghdad’s non-intervention by his colleagues, exiled, and soon murdered, marking another step in his rival Saddam Hussein’s ascent up the ranks. In Syria, meanwhile, the failed expedition was the last straw for the ruling junta, as defence minister Hafez Assad mounted a bloodless coup and set up a personalized dictatorship around his faction of the Baath, which tacitly assisted the marginalization of the fidayin over the next years. Finally, the ouster of Palestinians from Jordan also gave right wing Maronites a useful precedent to mount their own attack on the Palestinians in Lebanon, a major factor in the civil war that would erupt in the mid-1970s.

In the aftermath of the defeat, and particularly Jordan’s refusal to come to terms in 1971, the fidayin remained at cross-purposes. Arafat and Wazir, in particular, tried to set up a fidayin base in Lebanon, bolstered by a number of Jordanian military defectors who soon assumed top positions in the fidayin ranks to build a “state within” the Lebanese state: this included military commander Saad Sayel, Abu Moussa Muragheh, and Attaullah Attaullah.

But other fidayin – and by no means exclusively the Marxists – adopted different tactics, including hijack, murder, and sabotage. But Banna was only an extreme case: though Fatah had early condemned the Marxists’ inflammatory approach, revenge was a powerful motivator, and a number of Fatah commanders including Khalaf himself soon dabbled in spectacular acts of sabotage and murder, carried out by semi-independent networks named after “Black September”.

Black September had taught the fidayin a brutal lesson, since learned by other non-state militants in theatres as far-flung as Afghanistan, Syria, and Chechnya. Local popularity, rhetoric, and theory proved no match against the power of state repression – even a state as apparently fragile as Jordan. The irony was that the fidayin had dreamt of upstaging the Arab capitals in the war on Israel, but ultimately ended up relying on and being disappointed by them. Fragmentation, with the ensuing indecision and argumentation, was also fateful; not only did Marxist maximalism alienate the fidayin, but non-Marxist groups such as Fatah failed to capitalize on their fleeting opportunities to pre-empt the royal offensive.

The reality was that the majority of the fidayin, in spite of fringe rhetoric, never seriously intended to displace the crown, while the Jordanian regime, with the cold ruthlessness of state interests, ultimately did decide on and commit to their displacement. Especially when weighing the rebuffed attempts at reconciliation by the Palestinians in the winter of 1970-71, it is difficult to avoid the impression that, whatever the fidayin excesses, they were more sinned against than sinners: Black September saw a state use hook or crook to implement its monopoly of force.

Article by: Ibrahim Moiz