Spanish police have uploaded a video showing the seizure of a Russian oligarch’s boat on the Mediterranean island of Majorca last month by the FBI and the U.S. government on YouTube.

Viktor Vekselberg’s Tango, a $90 million yacht, was seized in a campaign against wealthy Russians with links to the Kremlin.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the United States has uncovered more than $1 billion in assets, including luxury boats, private jets, and works of art, all belonging to affluent associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The seizure was allowed by U.S. Magistrate Judge Zia Faruqui, who described the pursuit of the boat by a new Justice Department unit named task force kleptocapture as “only the beginning of the retribution that awaits anyone who would enable Putin’s atrocities.”

It might be a long before everyone knows the full extent of the damage. The simple part is seizing assets, whether it’s a boat or a bank account.

Civil forfeiture, a lengthy procedure requiring the government to show a judge that the assets were gained via criminal activity or money laundering, is normally required before the government may seize them permanently. After then, the assets become the property of the government, which gives it the authority to sell them.

If the previous owner defends the forfeiture proceedings in court, it may take years.

The White House revealed a proposal last week that would make it simpler for U.S. officials to go after some oligarch assets through an administrative procedure overseen by the Treasury Department, to expedite the transfer of confiscated assets to the Ukrainian government. Due process and fast federal court review are among the promises made by administration officials, despite the lack of specifics.

Proposals from the White House would alter the way the government deals with large-scale asset seizures. Administrative forfeiture is most commonly utilised in less publicised situations, involving assets worth less than $500,000. As far as we know, affluent Russians are not putting their money in US bank accounts or in hedge funds and private equity businesses.

Franklin Monsour Jr., a former federal prosecutor and a white-collar defence lawyer at Orrick in Uncharted York City, said, “The thought of a yacht or aircraft worth in the hundreds of millions seized and liquidated administratively is new ground.”

According to Monsour, the administration and Congress may bet on the fact that many Russian oligarchs would not mount a court challenge to a new, faster procedure since doing so would expose them to U.S. law.

“It will not be a problem,” he remarked. “The government is aware of this.”

Monsour noted that even if prosecutors must use the more traditional civil forfeiture procedure sometimes, the lawsuit may go more quickly than usual for the same reason.

A rise in the frequency of seizures may be on the horizon.

Russian gold mogul Suleyman Kerimov’s $300 million mega-yacht was confiscated by officials in Fiji collaborating with the task force on Thursday, according to prosecutors.

This is a sign, however, that the task force may be hesitant in some circumstances to reveal its methods for tracking down assets, as seen by the substantially redacted affidavit that accompanied the seizure of assets.

The government has an incentive to expedite the forfeiture procedure if the assets it seizes are expensive.

The value of the luxury real estate will decrease if it is not adequately maintained before it is sold to another member of the restricted group of individuals who can afford it.

There will be money spent on maintaining yachts that are sitting in ports, according to financial crimes expert Daniel Tannebaum, a former Treasury official and Oliver Wyman consultant.

As one analyst put it, “These assets may sit for an exceedingly long period.”

According to American officials, though, they are hoping to do more than merely confiscate the wealth of oligarchs. Undermining Russia’s financial infrastructure is one aim, says Assistant Secretary of Treasury for Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes Elizabeth Rosenberg.

A parade of shell companies in locations like the British Virgin Islands has been used throughout the years by Russia and its oligarchs to shift money from Cyprus and the Cayman Islands to Jersey in the Channel Islands, all of which have a long and well-documented reputation as tax havens. There will be an investigation into whether oligarchs are attempting to illicitly avoid sanctions by moving money and property to an unrestricted individual or business organisation.

For unlawfully moving $10 million from a U.S. bank to a Greek business partner, federal authorities in Manhattan filed criminal accusations against Konstantin Malofeyev.

Russia imposed sanctions on Malofeyev in 2014 following its invasion of Crimea, a portion of Ukraine that it eventually annexed, since he had lately called the Russian invasion of Ukraine “holy war.”

Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska’s Washington residence was searched by federal officials in October, and an assortment of valuables, including an oil painting by Diego Rivera, were taken.

Bloomberg reported last month that authorities had taken action in response to allegations that Deripaska was seeking to avoid sanctions by shifting some of his money around.

In reaction to Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, the United States imposed sanctions on Deripaska, an industrialist with strong links to Vladimir Putin. Since then, US officials have been pursuing Deripaska’s assets. The sanctions designation had made him “radioactive” in the business community, according to Deripaska, who sued the United States government a year later. A federal appellate court denied his appeals six weeks ago.

Over the past few months, Treasury Department sanctions have been placed on over 530 Russians with ties to the Kremlin. A large part of the past work of the new kleptocapture task force has been “unprecedented” information sharing regarding those people with US financial businesses, Treasury authorities and abroad criminal enforcement agencies, according to federal prosecutor Andrew Adams.

Even if the task force does not take ownership of an item, Adams, a senior federal prosecutor in Manhattan who has worked on money laundering and asset forfeiture cases, said the task force may make it impossible for the owner to utilise it.

When Adams was a prosecutor, “I considered a victory to be a conviction,” he remarked. When it comes to oligarchs’ yachts, “it may convince an insurance provider to revoke their policy coverage.”

According to Adams, the government can confiscate assets as part of a criminal case but is unlikely to do so. As a result, the White House is considering a civil process or a sped-up administrative procedure that requires the arrest and conviction of its proprietors.

A civil forfeiture process also needs proof of criminal action on behalf of the government.

According to Faruqui, the federal government had shown reasonable cause that Vekselberg gained Tango using “illicit revenues and laundered monies,” which is why he approved the seizure of the boat. Prosecutors must prove Vekselberg committed bank fraud, money laundering, or any other crime before they may permanently confiscate his assets.

Global efforts to confiscate affluent Russians’ assets have taken place mostly in European and Caribbean countries, notwithstanding the sanctions imposed by the United States.

Since February, the European Union has blocked assets linked to Russian billionaires totalling almost $30 billion. Just a few weeks ago, British officials revealed they had blocked $13 billion in assets linked to one of them:

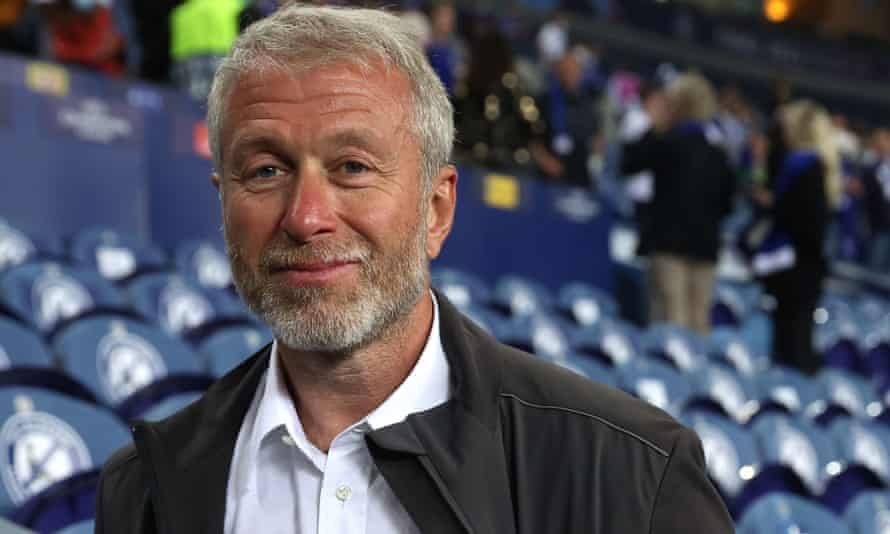

Roman Abramovich

Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich, the longtime owner of Chelsea Football Club in London, has been under considerable criticism from British authorities. After agreeing to split ways with the squad in March as the government was getting ready to levy fines, the club announced on Friday that it had approved a $3 billion deal from a group of purchasers. This is the biggest fee ever paid for a sports franchise, and the money will go into a British bank account that has been blocked.

U.S. officials have not sanctioned Abramovich, who spent billions of dollars with offshore funds managed by American corporations and holds stakes in many American steel mills, partly because he acted as a go-between in talks between Ukraine and Russia. Adams refused to comment on the issue.

His team’s research on Russian billionaires has found that they have fewer assets in the United States than in other nations. He provided a reason for this. Some were frightened away by Treasury sanctions imposed seven years ago after Russia invaded Crimea. According to Adams, penalties have been in place since 2014. In the past, “We have not been a welcoming place to put your money.”