Balochistan stands at a critical juncture in its administrative and developmental journey. As Pakistan’s largest province by landmass, yet one of the least administratively integrated, Balochistan continues to struggle with governance gaps that stem not from a lack of potential, but from geography, history, and structural imbalance. Sprawling mountains, scattered populations, harsh terrain, inadequate infrastructure, border complexities and a concentration of governance in a single provincial center have collectively restricted the province’s ability to govern effectively.

A compelling proposition is now emerging: reorganizing Balochistan into four administrative regions, each designed around geographic logic, socio-economic cohesion, security realities and population distribution. This structural redesign aims to decentralize authority, enhance service delivery, strengthen local economies and bring government closer to communities long cut off from decision-making.

A Historical Backdrop: Why Administrative Reform Has Become Necessary

To understand why Balochistan requires a new governance model, one must revisit the province’s layered past.

Early Civilizations and Tribal Structures

Archaeological sites such as Mehrgarh, dating back to around 7000 BCE, establish Balochistan as one of the world’s earliest centers of settled agriculture. Across millennia, waves of migration, trade routes linking Persia and South Asia, and the rise of various tribal confederacies — Baloch, Brahui and Pashtun — shaped a region defined by diversity rather than uniformity.

These tribal systems fostered local autonomy and collective decision-making, but they also evolved independently across vast distances, creating distinct northern, central and coastal socio-political worlds.

Colonial Fragmentation

Under British rule, Balochistan was divided into administratively separate domains:

- The Chief Commissioner’s Province, encompassing directly administered territories;

- The Baloch princely states, including the Khanate of Kalat, which retained internal sovereignty in return for cooperation and external allegiance.

This bifurcated system created uneven governance traditions that outlived colonial rule.

One Unit and Beyond

The imposition of the One Unit system (1955–1970), which merged all western provinces into a single administrative entity, diluted provincial autonomy and destabilized existing governance networks. When Balochistan was formally recognized as a separate province in 1970, its administrative foundations were incomplete, under-resourced and geographically mismatched.

Efforts to improve internal governance led to the creation of several divisions — Quetta Division, Kalat Division, Makran Division, Zhob Division, Nasirabad Division and, more recently, Rakhshan Division. However, despite these adjustments, the province’s overwhelming size and natural barriers continue to obstruct efficient administration.

Why a New Administrative Model Is Needed Now

Balochistan’s current administrative structure is insufficient to address its complexities. Several fundamental challenges underscore the need for a reorganisation:

- Geography Outpaces Governance

Much of Balochistan is mountainous, inter-montane or desert terrain: about 80% of the province is classified as inter-mountainous, with only 20% comprised of floodplains or coastal plains. Many districts lie hours, sometimes an entire day, away from existing divisional headquarters. Large parts of the province remain physically inaccessible during harsh weather or because of poor road networks. Managing security, healthcare, education, and justice from a distant central authority is simply impractical.

- Population Is Thin, but Distances Are Vast

Despite covering roughly 44% of Pakistan’s land area, Balochistan remains the least densely populated province: only around 12–14 persons per square kilometer in many areas. Even though Balochistan hosts a small population relative to its size, its inhabitants are distributed unevenly, with clusters in highlands, pockets in plains, and scattered settlements across deserts and coastal stretches. This demands regionalized governance rather than centralized control.

- Economic Potential Is Region-Specific

Agriculture, mining, cross-border trade, livestock, fishing, port development and desert minerals are not evenly distributed. Different zones require tailored policies that reflect their unique natural resources and challenges. Under a uniform administrative structure, the priorities of one zone, say coastal development, are unlikely to get sufficient attention among competing needs from the highlands, deserts or plains.

- Security Pressures Are Uneven

Border management with Iran and Afghanistan, smuggling routes, tribal disputes, insurgency hotspots, and emerging economic corridors all require region-specific security coordination. A single command center cannot adequately address these nuances. Moreover, neglect and perceived injustice in distant regions have historically fueled local grievances and instability.

- Representation and Trust Deficit

Communities geographically distant from provincial capital often feel alienated from governance. They lack ready access to government offices, administrative services, and political participation. Bringing administration closer can rebuild trust and ensure that people view the government as part of their daily lives rather than a distant authority.

These challenges form the backdrop for a well-structured proposal to reorganize Balochistan into four administrative regions — each grounded in geographic logic, demographic continuity and economic synergy.

To better understand why Balochistan’s administrative challenges require structural reform, it is useful to compare the province with international regions of similar or even smaller size.

Comparative Perspective: How Regions Smaller Than Balochistan Thrive Through Administrative Division

A useful way to understand the necessity of new provinces in Balochistan is to view it through a global comparative lens. With an area of approximately 347,190 square kilometers, Balochistan is not only Pakistan’s largest province but is also geographically larger than numerous fully sovereign and economically advanced nations. Countries such as Poland (312,000 sq km), Italy (301,000 sq km) and the Philippines (300,000 sq km) are significantly smaller, yet each one consists of multiple administrative, political, and economic tiers that ensure effective governance and service delivery across their territories. These nations demonstrate that large populations are not a prerequisite for strong development; rather, administrative proximity, decentralized authority, and resource-responsive governance drive progress.

Globally, even countries with complex ethnic or geographic compositions—such as Turkey, which has 81 provinces despite being slightly larger than Pakistan, or Nigeria, which operates 36 states within roughly half of Pakistan’s land area—attest to the principle that smaller administrative units create stability and accelerate development. These countries have recognized that governance improves when authority is localized, when citizens can reach administrative centers easily, and when political attention is distributed rather than concentrated.

India’s experience further strengthens this argument. The division of Punjab into Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh, and later the creation of states like Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Telangana, resulted in sharper administrative focus and more equitable development. Smaller states were able to cultivate specialized economic strengths, develop targeted policies, and provide public services more efficiently.

In contrast, Balochistan—with its vast distances, scattered settlements, and challenging terrain—remains governed as a single unit. No country or province of comparable size relies on a centralized model and simultaneously achieves balanced development. The global evidence is clear: where territories are large, geographically diverse, or historically underserved, subdivision is not merely desirable—it is essential. A more granular administrative map of Balochistan would align the province with international best practices and unlock the development potential currently suppressed by scale, distance, and centralization.

These global examples clearly demonstrate that Balochistan cannot achieve balanced governance under a single administrative unit, which makes the case for new provincial divisions even stronger.

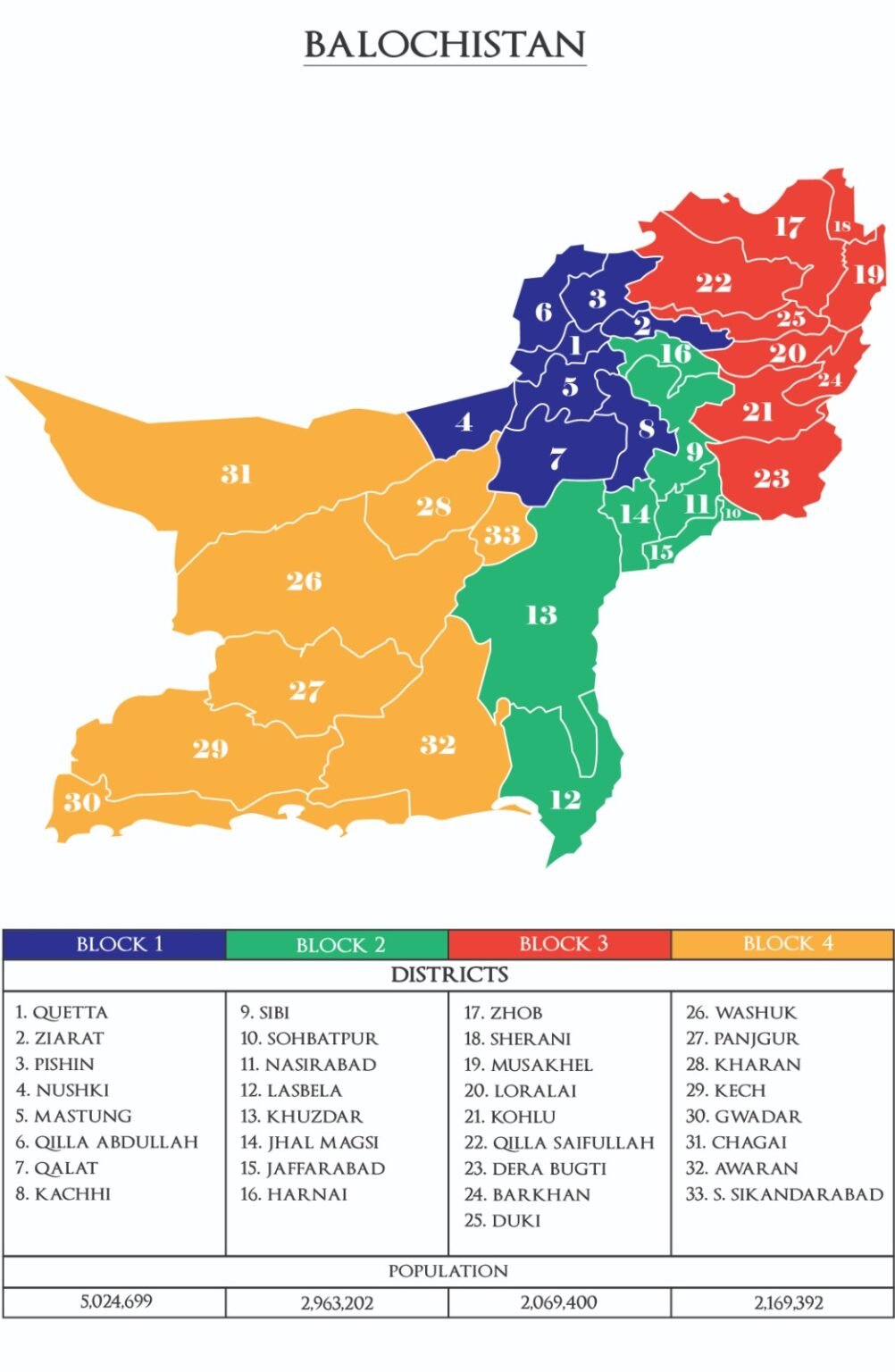

The Four Proposed Administrative Regions

The proposed model divides Balochistan into four contiguous administrative regions, each consisting of districts that share natural terrain, socio-economic patterns, travel networks and cultural links. Each region also carries specific population and land area metrics, demonstrating the balance between governance load and geographic realities.

Block 1: The Quetta-Centered Administrative Hub

Districts:

Quetta, Ziarat, Pishin, Nushki, Mastung, Qilla Abdullah, Qalat, Kachhi

Population: 7,015,526

Region Overview

Region One forms the political, administrative, and economic core of Balochistan. Quetta, as the provincial capital, anchors the region and hosts major educational institutions, hospitals, administrative departments, and transport hubs.

Strategic Significance

- Serves as Balochistan’s primary administrative and political nerve center.

- Functions as a service hub for northern, central, and parts of eastern Balochistan.

- Provides cross-border connectivity with Afghanistan via major routes.

- Contains agricultural and orchard belts (Pishin, Ziarat) alongside semi-urban growth zones (Mastung, Qalat).

- Has the capacity to absorb rural–urban migration if urban planning is strengthened.

Governance Goal

To reduce excessive centralization in Quetta by creating empowered district-level administrative nodes. Strengthening secondary cities will relieve urban pressure, promote even development, and improve service accessibility for remote populations.

Block 2: The Agricultural–Industrial and Mineral Corridor (Block 2)

Districts:

Sibi, Sohbatpur, Nasirabad, Lasbela, Khuzdar, Jhal Magsi, Jaffarabad, Harnai

Population: 2,963,202

Region Overview

Region Two stretches from densely cultivated plains to mineral-rich uplands. It contains Balochistan’s most productive agricultural zone and connects major north–south and coastal trade pathways.

Economic Highlights

- Nasirabad, Jaffarabad, and Sibi form Balochistan’s agricultural heartland and are vital for food security.

- Khuzdar and Lasbela possess significant mineral potential and industrial linkages.

- Jhal Magsi and Sohbatpur contribute to livestock and mixed agriculture.

- Harnai offers coal, livestock, and horticultural potential.

- The region forms a logistical corridor between northern and southern Balochistan.

Administrative Importance

With large population concentrations in agricultural plains and vast mineral belts in the southeast, this region benefits from decentralized governance that can:

- Improve water distribution and agricultural planning.

- Regulate mineral extraction with transparency.

- Strengthen transportation links and inter-district trade networks.

- Enhance disaster-management and climate resilience in flood-prone plains.

Block 3: The Highland Tribal Belt

Districts:

Zhob, Sherani, Musakhel, Loralai, Kohlu, Qilla Saifullah, Dera Bugti, Barkhan, Dukki

Population: 2,069,400

Region Overview

Region Three encompasses the northeastern highlands, characterized by rugged terrain, tribal administrative structures, and historical developmental gaps.

Key Features

- Tribal systems play a central role in conflict resolution and social governance.

- Geographic isolation creates severe gaps in infrastructure, health access, and market connectivity.

- Contains border-adjacent and security-sensitive regions.

- Holds major mineral prospects—especially in Kohlu and Dera Bugti—which remain underutilized due to limited access and stability issues.

Governance Objectives

- Build mountain-adapted road networks and micro-irrigation systems.

- Expand mobile healthcare, tele-education, and community-based schooling.

- Integrate tribal governing structures with formal administration using a hybrid governance model.

- Promote local economic opportunities to reduce migration and foster stability.

Block 4 : The Coastal–Desert Strategic Frontier

Districts:

Washuk, Panjgur, Kharan, Kech, Gwadar, Chagai, Awaran, S. Sikandarabad

Population: 2,169,392

Region Overview

Region Four spans the deserts of western Balochistan and the globally significant Makran coastline. The region includes Gwadar — a linchpin of emerging global maritime and economic corridors.

Economic and Strategic Assets

- Gwadar Port: A strategic deep-sea port with potential to transform trade, logistics, fisheries, and shipping industries.

- Chagai Mineral Belt: Home to Reko Diq and world-class copper–gold deposits that attract major international interest.

- Makran Coastline: Offers opportunities in maritime trade, fisheries, coastal tourism, and blue-economy development.

- Desert Districts: Ideal for large-scale solar and wind energy investments.

Governance Priorities

- Ensure equitable community benefits from port-driven development through employment, revenue-sharing, and service expansion.

- Build climate-resilient infrastructure suited to coastal storms, cyclones, and desert conditions.

- Implement transparent frameworks for mineral extraction, environmental safeguards, and localized reinvestment.

- Modernize border trade governance to maximize legitimate commerce and reduce smuggling.

How the Four-Region Model Addresses Balochistan’s Key Challenges

Each proposed region is designed not only to group together geographically contiguous districts, but also to create administrative coherence, reduce burdens on the provincial capital, and promote balanced development across the province. Below are the core benefits such a reorganization can deliver:

- Administrative Decentralization and Closer Governance

- By creating smaller administrative regions, governance becomes more accessible. Districts that currently lie dozens—or hundreds—of kilometers from provincial headquarters would gain regional capitals, shortening travel time for citizens needing to access government offices.

- This proximity reduces travel costs, increases accountability, and fosters local ownership. For example, instead of travel to Quetta for a mining license, a district in the desert mining belt could apply to a regional administrative office within Region Four.

- Region-Specific Economic Growth Plans

- Economic planning tailored to each region’s strengths — whether agriculture, mining, coastal trade, or highland pastoralism — ensures resources are used efficiently.

- Region Four can adopt a “maritime and mineral frontier” strategy; Region Two can focus on agriculture, agro-processing, and mineral corridor infrastructure; Region Three can prioritize mountain agriculture, livestock, and trade linkages; Region One can modernize urban governance, services, and connectivity.

This specialized approach is far more effective than a one-size-fits-all provincial plan.

- Enhanced Security Coordination

- Security threats — insurgency, smuggling, tribal conflict, cross-border movement — are often localised. Regional authorities, familiar with terrain and social dynamics, can coordinate more effective border patrols, intelligence gathering, and liaison with tribal leaders.

- Localized civil-military coordination, supported by dedicated regional institutions, can respond more quickly to emerging unrest than a distant central command.

- Fairer Distribution of Resources & Local Empowerment

- Under the new model, revenue from ports, mineral leases, fisheries and trade can more easily be allocated to local development budgets rather than being absorbed centrally.

- Local assemblies and governing bodies can ensure that communities have direct say over resource use, employment, land rights and environmental protection — reducing feelings of exploitation and marginalization.

- Reduced Inter-Tribal and Regional Friction

- Because the proposed regions group districts largely along natural, geographic, tribal and cultural lines, administrative boundaries coincide with social realities — reducing friction caused by forced, unnatural alignments.

- When administration reflects ground realities, ethnic or tribal grievances (about representation, neglect, or resource distribution) are less likely to arise.

Risks and Challenges — And How to Mitigate Them

No administrative reform is without challenges. Honest assessment is needed to ensure success.

- Political Resistance

Existing power centres — tribal sardars, entrenched elites, influential political families — may resist structural change fearing loss of influence.

Mitigation: A phased approach, inclusive consultations with tribal leaders, civil society, community elders and youth, and transparent transition plans. Constitutional safeguards for civil service continuity, fair representation in new regional assemblies, and public participation in boundary demarcation can reduce resistance.

- Budget and Infrastructure Costs

Setting up new administrative centres, regional capitals, bureaucracies, infrastructure (offices, roads, utilities) demands resources that the provincial budget may struggle to provide.

Mitigation: Initially adopt interim divisional secretariats — modest offices empowered to coordinate basic governance — rather than full-fledged provincial structures. Use e-governance to reduce overhead. Mobilize federal development grants, public-private partnerships, and revenue-sharing agreements (especially from mineral and port revenues) to finance infrastructure.

- Risk of Inter-Regional Inequity

Some regions may flourish quickly (e.g., coastal or mineral-rich), while others — especially sparsely populated highlands — may struggle to generate revenue. This disparity could create new inequalities.

Mitigation: Institute a provincial equalization fund, funded by revenues from prosperous regions (mining, port, trade) to support poorer regions until they stabilize. Prioritize human development (health, education) in all regions to ensure baseline equity.

- Administrative Capacity and Human Resources

New administrative units will need trained personnel — civil servants, local bureaucrats, law enforcement — which are currently limited.

Mitigation: Launch recruitment and training drives prioritizing local youth. Use district-level capacity building, training academies, and periodic rotation — giving locals a stake in administration, while avoiding over-centralization.

- Public Perception & Social Acceptance

People accustomed to a single provincial identity may view regional divisions as fragmentation, or fear ethnic segregation.

Mitigation: Emphasize that the restructuring is administrative, not a redrawing of national boundaries. Maintain shared provincial identity while promoting regional empowerment. Public awareness campaigns, community engagement, inclusive planning and transparent communication will be key.

Implementation Roadmap — Turning Proposition into Policy

For such a major reform to succeed, a structured, phased approach is essential.

Phase 1: Legal and Administrative Framework

- Pass provincial legislation formally recognizing the four regions.

- Establish interim regional secretariats (not full provinces) with delegated budget and administrative powers — to pilot decentralized governance.

- Define boundaries clearly using census and cadastral data, and confirm district composition as per the four-region proposal.

Phase 2: Infrastructure and Digital Systems

- Begin building minimal administrative infrastructure (offices, communications, basic utilities) in regional capitals.

- Launch e-governance platforms to process documentation, applications, and citizen services — reducing need for physical travel.

- Upgrade road, transport and connectivity networks to link all districts with their regional hubs.

Phase 3: Regional Development Plans

Each region should craft a five-year socio-economic plan tailored to its strengths:

- Region Four: Port development, fisheries, mining, coastal infrastructure, renewable energy.

- Region Two: Agriculture, water management, agro-processing, mineral corridor planning.

- Region Three: Mountain agriculture, pastoralism, local crafts, cross-border trade, small-industry development.

- Region One: Urban infrastructure, education, health, transport, intra-regional connectivity, industrial hubs.

Implement monitoring and evaluation systems to track progress.

Phase 4: Public Engagement and Social Integration

- Conduct consultations with tribal elders, community leaders, civil society groups and youth representatives.

- Establish mechanisms for local participation: district councils, regional assemblies, resource-sharing forums, grievance redress mechanisms.

- Launch public information campaigns to explain the goals, benefits and safeguards of the new model — addressing fears of fragmentation or segregation.

Phase 5: Institutionalization and Consolidation

- Once interim secretariats show effectiveness, formalize regional administrations — possibly with enhanced autonomy — under provincial and federal frameworks.

- Establish resource-sharing agreements ensuring equitable distribution of revenue from mining, ports, trade and federal transfers.

- Prioritize human development, public services, infrastructure, and connectivity across all regions.

Toward a Shared Future: Four Regions, One Balochistan

This four-region administrative proposition for Balochistan is not an exercise in fragmentation — rather, it is a blueprint for equitable growth, inclusive governance and long-term stability in one of Pakistan’s most diverse and strategically critical provinces.

By acknowledging regional differences instead of forcing a uniform approach, this model promises to do justice to geography, history and the aspirations of communities long neglected. It seeks to repair the persistent disconnect between resource wealth and human development, between strategic importance and public welfare, between center and periphery.

If implemented with political will, transparent planning, constitutional clarity and strong community participation, this four-region model could transform Balochistan from a peripheral province into a network of regionally empowered zones — each thriving in its own right, yet united under a shared provincial and national identity.

In doing so, Balochistan can begin a new chapter: one of development, dignity and belonging. This is not just a proposition. It is a vision — and for Balochistan, a bold vision is long overdue.