One can only begin to imagine the innate nature of people who caused one of the most noticeable migrations in world history. A displacement of 10–20 million people (including 6.5 million), all rallied under one cause, one leadership: Mohammad Ali Jinnah. What does this depict about the people of Pakistan? That they are determined to fight for what they believe in and achieve it by any means possible, even at the cost of their lives. Quaid-e-Azam’s passing orphaned Pakistan not only of its Father, but also of its leader. This was the point when evident dispersion in Pakistani politics began, as they no longer had one person to look up to. As political parties increased in number, people started to align with those who voiced their thoughts best. Hence began the era of political polarisation in Pakistan.

Before the advent of social media, it was print media—newspapers and magazines—that shaped public opinion. The book Impact of Social Media on Political Polarisation in Pakistan launched by Islamabad Policy Research Institute(IPRI) is a thorough study of how platforms like Twitter (now X), Instagram, and Facebook have become forces that shape political narratives, allegiances, and divides in the country. The researchers used both qualitative interviews and quantitative data (Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient) to gauge agreement with the claim that “Social media has made the political sphere in Pakistan more polarized.”

From 2017 to 2025, social media users in Pakistan grew from 31 million to 66.9 million—a breakthrough in online engagement. In early 2025, internet penetration reached approximately 45.6% of the population, meaning 116 million users had access to a digital presence. According to research, this is about 26.4% of the total population. Platforms that once seemed like free spaces for opinions and ideas are actually algorithm-driven realms shaped to reinforce a user’s likes and dislikes. These environments create the illusion of “It’s me, my world, and I,” where users cannot see beyond their own ideologies—what we now refer to as echo chambers.

Echo chambers are like wells—you hear only your own voice echoing back. But on social media, visuals and repetition are used to hammer ideas, which enhances rigidity of thought. People rally around causes based solely on political, social, or cultural ideologies. According to The Express Tribune, the average Pakistani social media user is “literate, young, and affluent.” This demographic holds significant sway in political processes, which is why political parties now formally hire social media influencers to promote their narratives.

Social media may not be the root cause of political chaos in Pakistan, but it has certainly made it more volatile. According to Talha ul Huda, a digital media producer, social media acts as a catalyst in political polarisation, expanding both negative and positive sentiment. He adds that repeated exposure to short videos embeds ideas into peripheral memory, fuelling resentment. As the book states, “Social media didn’t invent polarization, but it exacerbates it.”

These findings are reinforced by the thoughts of Ammar Jafri (former Additional Director General of FIA and founder of E-Pakistan), who believes polarisation is the result of multiple factors, including state-driven narratives that conflict with public interests. Platforms like X and YouTube are used as tools by political parties, who know that algorithms prioritize content that spreads quickly. Instead of promoting positive conversation, misinformation and disinformation are deployed to gain political mileage—intensifying polarisation.

It feels like an online war, with warriors on both sides using their keyboards to fire digital missiles. Each side views the other as a “mortal threat” to its political survival. This behaviour starts at the top, with party leadership, and trickles down to grassroots levels. No one agrees that it is okay to disagree. Though the canker of polarisation is not limited to Pakistan, it extends globally. A study titled Polarisation and Populism found significant political polarisation in many European and Central Asian nations. Increasing numbers of voters are abandoning centrist positions, losing faith in established parties and institutions.

In Pakistan, social media is still a relatively new force in politics. Pakistani students follow political leaders to maintain parasocial relationships and feel more connected. Researchers Ali Khan, Farhat Ali, Muhammad Awais, and Muhammad Faran concluded that echo chambers amplify specific narratives. This reshaped political engagement among the youth. Instead of bridging gaps, the divide is left cleft.

The book Impact of Social Media on Political Polarisation in Pakistan by IPRI highlights the positive side of social media too—its role in advocacy and crowd mobilization. It spreads information about events and gatherings, benefiting NGOs, think tanks, and universities. A prime example was the 2007–2008 lawyers’ protest against Musharraf, where social media enabled coverage during state censorship. In 2014, PTI used #AzaadiMarch to rally support. The Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) also relied on Facebook Live to gain attention. Social media has indeed given a “voice to the voiceless”—especially to marginalized groups like women and the transgender community, through platforms and movements like the Aurat March.

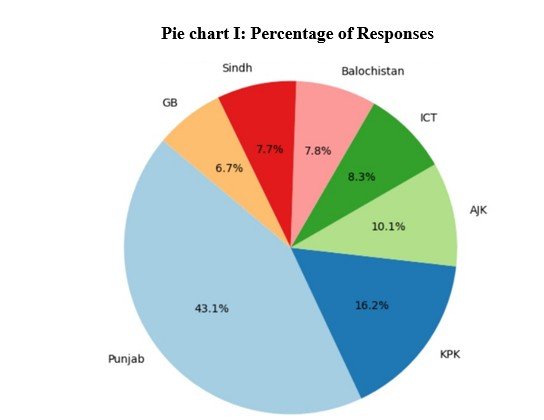

IPRI’s publication Impact of Social Media on Political Polarisation in Pakistan clearly states that the research was conducted in urban areas among people with English proficiency and stable internet connections. The survey was conducted through Google Forms, requiring a Gmail account. Urban centres like Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, and Rawalpindi dominate social media use, while rural regions lag due to poor infrastructure, high maintenance costs, and loadshedding. Another key factor is gender disparity—70% of social media users in Pakistan are male, highlighting digital inequality. The book also notes that platforms like TikTok and YouTube are flourishing, while X saw a decline of 2.5 million users in one year.

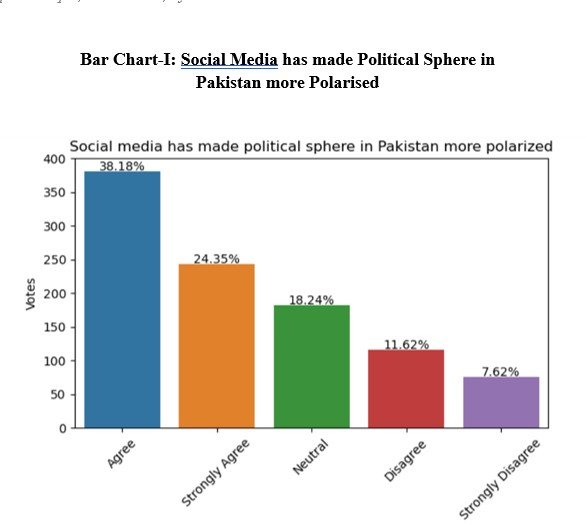

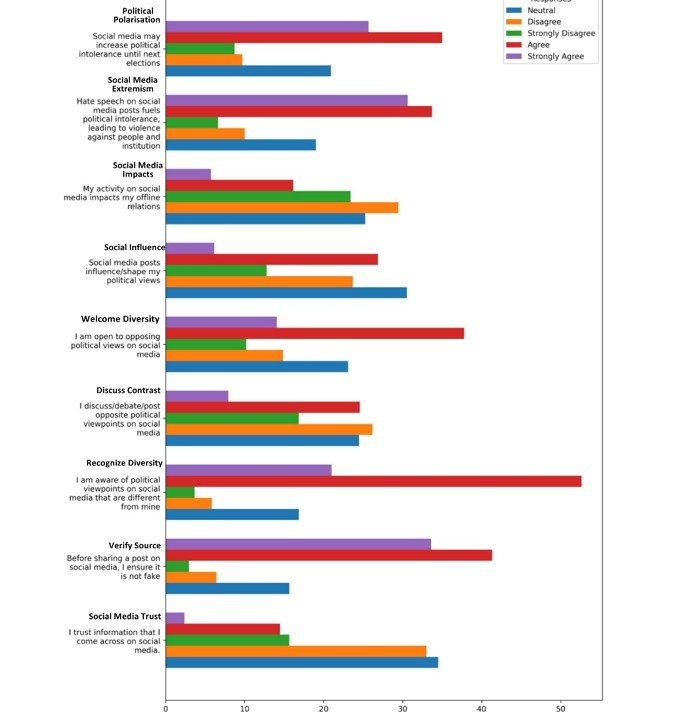

Using Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient, the book supports its claim: over 62% of participants—largely young, literate, and urban—believe social media has made politics more polarised. X showed the strongest impact on shaping political opinion, TikTok a weak negative correlation, and platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram showed negligible effects. These results show how platform design and user behaviour differently impact political discourse.

The emotional and psychological dynamics of polarisation are explored in the book. Referencing Emilia Palonen’s observation that “polarisation generates an us versus them dynamic,” the book shows how Pakistani society increasingly views political differences as existential threats. Leadership plays a central role—party heads ignite rhetoric that trickles down to grassroots supporters. Roderick Rekker’s insight is also included: “People tend to disregard information that contradicts their political identity,” reinforcing that polarisation is as much psychological as political.

The book includes expert insights like those of Iqra Ashraf, former Director of Strategic Communication at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who described the link between social media and political organisation as “complex and multifaceted.” While social media may seem democratic by giving voice to the voiceless, it also breeds emotionally charged content, creating smokescreens and loops of outrage. According to Shabbir Hussain, Associate Professor at Bahria University, anonymity and a lack of accountability on social media embolden users to deepen social rifts without consequence.

The research acknowledges its limitations but still provides valuable insights into which demographics dominate social media use. However, the platforms that empower voices also manipulate them. As The Social Dilemma warned: “If you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product.” Algorithms exploit emotional responses, creating viral moments that aren’t always truthful. Tristan Harris’s chilling words resonate: “You don’t have to overwhelm people’s strengths. You just have to overwhelm their weaknesses… This is checkmate on humanity.”

As political analyst Anatol Lieven aptly noted, “The danger is that the political elites, in order to cling to power, are destroying the very idea of a national community.” This aligns with the book’s central argument: that political actors are manipulating digital platforms not for unity, but for division.

The book doesn’t just highlight the problems—it also suggests solutions. It recommends enhancing digital literacy across age groups to help users identify disinformation, misinformation, and fake news. It also calls for stronger libel laws, the embedding of fact-checking tools within apps, and the development of indigenous platforms that reflect local values. Moreover, it emphasizes that platforms must be held accountable for spreading harmful content. Online discourse should shift from divisive politics toward crucial issues like education, climate change, and economic reform—topics that foster meaningful engagement across generations.

Overall, Impact of Social Media on Political Polarisation in Pakistan by IPRI is a timely and necessary read. It educates the average user about the risks of digital manipulation and urges responsible usage for the safety of the state and society. More than an academic exercise, this book is a call to action. It compels political leaders, educators, tech developers, and citizens to come together and reshape social media from a divisive battlefield into a unifying space for dialogue, empathy, and national progress.

This book is authored by Iqra Siddique, Faizan Riaz, Syed Hassan Ahmed, and Noreen Akhter.All the images included in the article are taken from the book published by Islamabad Policy and Research Institute(IPRI) : Impact of Social Media on Political Polarization in Pakistani .IPRI is a Pakistani think tank focused on policy-oriented research, or Indigenous Peoples’ Rights International, an organization advocating for indigenous rights