From Biryani to Pulao, Pakistan and India’s shared culinary landscape is defined by Basmati, a distinctive long-grain rice now at the centre of the latest tussle between the bitter rivals.

India has applied for an exclusive trademark that would grant it sole ownership of the Basmati title in the European Union, setting off a dispute that could deal a major blow to Pakistan’s position in a vital export market.

“It’s like dropping an atomic bomb on us,” said Ghulam Murtaza, co-owner of Al-Barkat Rice Mills just south of Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city.

Pakistan immediately opposed India’s move to gain Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) from the European Commission.

India is the largest rice exporter in the world, netting $6.8 billion in annual earnings, with Pakistan in the fourth position at $2.2 billion, according to UN figures.

The two countries are the only global exporters of Basmati.

“(India) has caused all this fuss over there so they can somehow grab one of our target markets,” said Murtaza, whose fields are barely five kilometres (three miles) from the Indian border.

“Our whole rice industry is affected,” he added.

From Karachi to Kolkata, Basmati is a staple in everyday diets across southern Asia.

It is eaten alongside spicy meat and vegetable curries, and is the star of the endlessly varied Biryani dishes featured at weddings and celebrations across both countries, which only split following independence from British colonial rule in 1947.

They have since fought three wars, with the latest skirmish in 2019 involving the first cross-border airstrikes in nearly 50 years.

Diplomatic relations have been tense for decades and both countries routinely attempt to malign each other on the international stage.

Pakistan has expanded Basmati exports to the EU over the past three years, taking advantage of India’s difficulties meeting stricter European pesticide standards.

It now fills two-thirds of the region’s approximately 300,000-tonne annual demand, according to the European Commission.

“For us, this is a very, very important market,” says Malik Faisal Jahangir, vice-president of the Pakistan Rice Exporters Association, who claims Pakistani Basmati is more organic and “better in quality”.

PGI status grants intellectual property rights for products linked to a geographic area where at least one stage of production, processing, or preparation takes place.

Indian Darjeeling tea, coffee from Colombia and several French hams are among the popular products with PGI status.

It differs from Protected Designation of Origin, which requires all three stages to take place in the concerned region, as in the case of cheeses such as French brie or Italian gorgonzola.

Such products are legally guarded against imitation and misuse in countries bound by the protection agreement and a quality recognition stamp allows them to sell for higher prices.

India says it did not claim in its application to be the only producer of the distinctive rice grown in the Himalayan foothills, but attaining PGI status would nevertheless grant it this recognition.

“India and Pakistan have been exporting and competing in a healthy way in different markets for almost 40 years… I don’t think the PGI will change that,” Vijay Setia, former president of the Indian Rice Exporters Association, told AFP.

As per EU rules, the two countries must try to negotiate an amicable resolution by September, after India asked for a three-month extension, a spokesman for the European Commission told AFP.

“Historically, both the reputation and geographic area (for Basmati) are common to India and Pakistan,” says legal researcher Delphine Marie-Vivien.

“There have already been quite a few cases of opposition to geographical indication applications in Europe, and each time a compromise has been found.”

After years of procrastination, the Pakistani government in January demarcated where Basmati can be harvested in the country.

It also announced it would assign similar protected status to pink Himalayan salt and other vaunted agricultural products.

Pakistan hopes to convince India to instead submit a “joint application” in the name of the common heritage that Basmati represents, Jahangir said.

“I am confident that we will reach a (positive) conclusion very soon… the world knows that Basmati comes from both countries,” he added.

If an agreement cannot be reached and the EU rules in India’s favour, Pakistan could appeal to the European courts, but the long review process could leave its rice industry in limbo.

Pakistan receives GI tag for Basmati

The Rice Exporters Association of Pakistan (REAP) has announced that Pakistan received the geographical indication (GI) tag for its Basmati rice on January 26, 2021.

Consequently, Pakistan has managed to save approximately $1 billion in export revenue, which the country gets through export of Basmati rice to the European Union.

Taking to his official Twitter handle, Adviser to Prime Minister on Commerce and Investment Abdul Razak Dawood confirmed the development.

In his tweet, Dawood said, “He is glad to inform that Pakistan has registered Basmati rice as GI under the GI Act 2020. Under this Act, a GI registry has been formed, which will register the GI and maintain basic record of properties and authorised users.”

The adviser added, “This will provide protection to our products against misuse or imitation, hence, will guarantee that their share in the international market is protected.”

The International Property Organisation (IPO) Pakistan had filed its opposition under Article 51 of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 through a Brussels-based international law firm.

India had applied for GI tag under Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European parliament and council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs, mentioned in the EU official journal dated September 11.

According to Pakistan’s rice exporters, India currently has a larger Basmati rice share of around 65% in the EU whereas Pakistan has a 35% share in the European market. Pakistan’s total rice exports in 2020 stood at $2.2 billion. GI Committee Convener Sameeullah Naeem, while talking to The Express Tribune, said that the fresh development would open new avenues for Pakistan’s Basmati rice in other markets as well. “This is the first Pakistani product which has been registered under the GI tag and we can now claim and market our products in global markets,” Naeem said.

“We are now hopeful that we can increase the reach of local Basmati in export markets and believe that the government will create more opportunities to enhance our export revenue from rice,” he added.

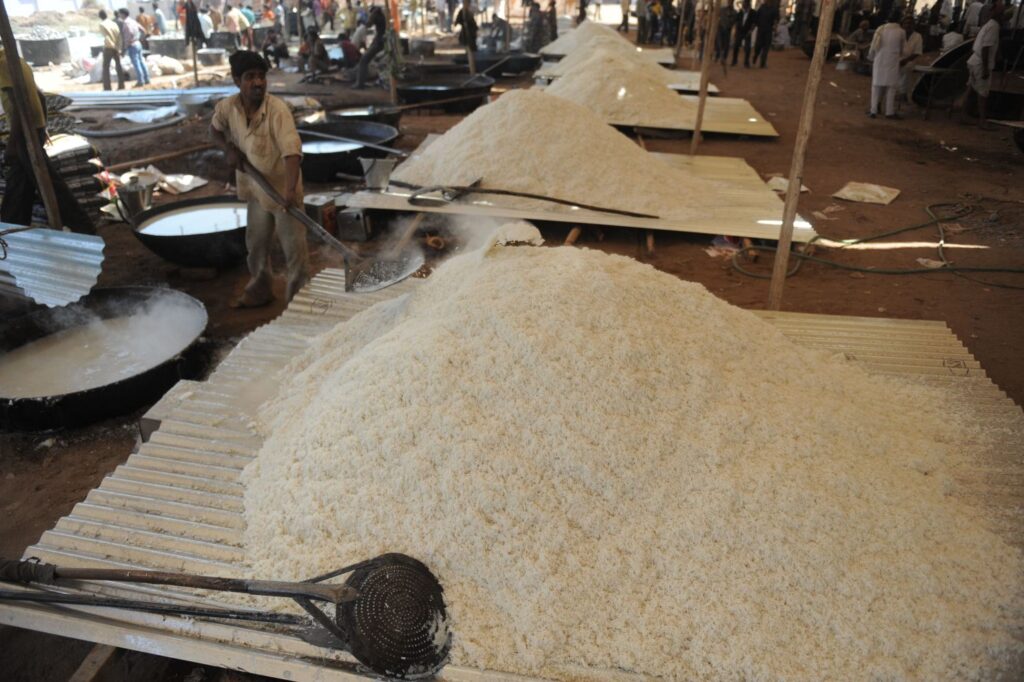

On the other hand, REAP claimed that they had made a major contribution to preparing the book of specifications for Basmati. “This book of specifications lays down the criteria of characteristics for Basmati rice, which should be followed by producers or operators in Pakistan if they desire to obtain a licence to use this name,” the association said.

The registration of Basmati as GI in Pakistan required cooperation between the public and private sectors.

The Trade Development Authority of Pakistan (TDAP) was designated as a registrant of Basmati rice by the federal government. TDAP made an application for registering Basmati to the IPO, which sought assistance of the Rice Research Institute Kala Shah Kaku and REAP. IPO mapped the regions where Basmati was grown by taking recommendations from all provinces. The process followed by IPO had been inclusive and brought all the stakeholders on board.

Through inter-provincial and public-private cooperation, Pakistan obtained GI tag for its Basmati, which would strengthen the case against India in the EU. Since Basmati fetches higher prices than non-basmati rice in the international market, India has attempted to block Pakistan’s trade with the EU by declaring that its Basmati is geographically the original one.

Pakistan has challenged this claim by registering its GI for Basmati. Furthermore, it will claim the same protection for its Basmati in the EU as India did.