Solar Mystery

For over four centuries, sunspots have intrigued astronomers since Galileo first documented them through his telescope in the early 1600s. These dark, cooler patches on the Sun’s surface can linger for days, sometimes even months, defying easy explanation.

Scientists have long wondered what allows these seemingly unstable features to remain intact for such long periods on the dynamic, turbulent surface of the Sun. Now, a groundbreaking study has finally unraveled the mystery.

Published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, the new research presents a major scientific breakthrough led by an international team of solar physicists, primarily based at Germany’s Institute of Solar Physics. The team has developed an advanced method to study sunspots, revealing the precise physical balance that holds them together. This long-awaited discovery solves a puzzle that has persisted for more than 400 years.

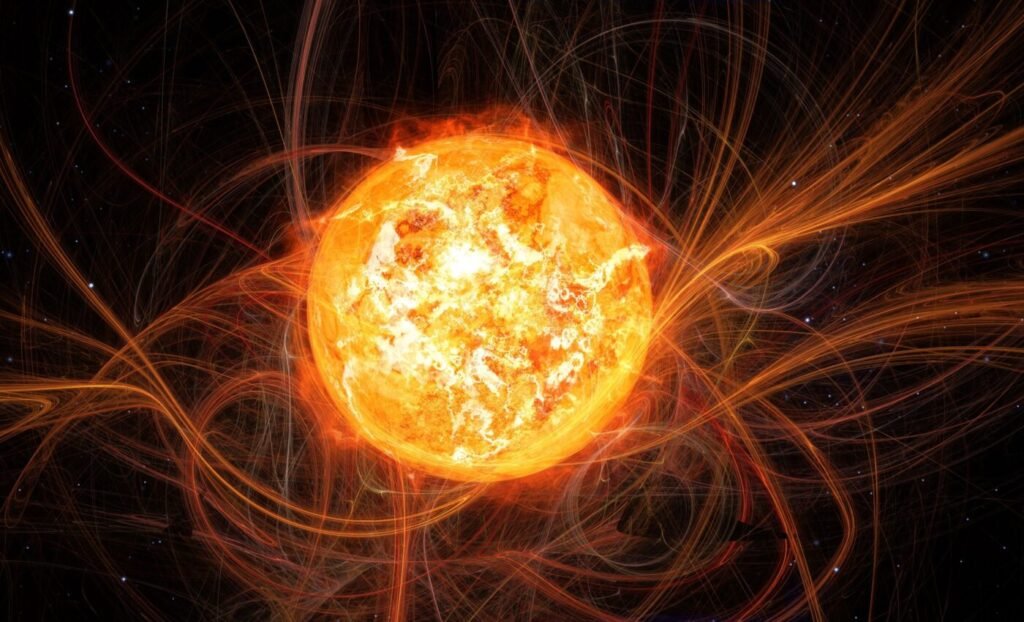

Sunspots are not simply blemishes on the solar surface. They are areas of intense magnetic activity — so powerful, in fact, that their magnetic fields rival those used in hospital MRI machines. Despite appearing dark against the Sun’s brilliant disk, a sunspot isolated in space would still shine brighter than the full Moon.

These regions, often larger than the Earth itself, are cooler than their surroundings and emerge in cycles roughly every 11 years, peaking during periods of maximum solar activity. During these peaks, sunspots are often associated with explosive solar events like coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and solar flares, which can interfere with satellites, GPS systems, and even Earth’s power grids.

The longstanding theory has suggested that sunspots maintain their stability due to an equilibrium between gas pressure and magnetic forces. However, until now, confirming this hypothesis has been difficult due to the interference caused by Earth’s atmosphere during solar observations.

To overcome this challenge, the research team improved upon an existing technique developed at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research. They applied this refined method to data collected from the German GREGOR solar telescope, Europe’s largest solar observatory. This innovation effectively removed the atmospheric distortion that previously hindered accurate measurements, allowing for near-satellite quality data to be collected from a ground-based telescope — at a significantly lower cost.

By analyzing the polarised light emitted from sunspots, the scientists could directly measure the magnetic field strength and internal pressure forces with unmatched precision. Their findings confirmed that sunspots persist because the magnetic forces within them are in perfect equilibrium with the surrounding gas pressure. This delicate balance is what allows sunspots to remain stable for long durations, despite the constantly shifting solar environment.

Beyond solving a centuries-old mystery, the implications of this research are highly practical. A deeper understanding of sunspot stability could lead to improved forecasting of solar activity and space weather events.

With better prediction models, scientists could offer earlier warnings about solar flares and CMEs that might threaten satellites, disrupt power grids, or endanger astronauts in space.

As modern life becomes increasingly reliant on space-based and electronic technologies, such insights are not just scientific milestones but also vital tools for protecting infrastructure and human life. This discovery marks a major advancement in solar physics and stands as a testament to the power of innovative observation techniques combined with international scientific collaboration.